In the paintings and drawings of Lalu Prasad Shaw, the line- unfaltering, tensile- speaks. The elegant, stylized portraits of men and women of the Bengali middle-class, which have become his hallmark, draw us into a world defined by the artistic line. The figures are portrayed ostensibly in postures of repose or relaxation – even walking appears to be a state of suspended animation -and sometimes in the manner of a posed photograph. But they contain a sense of restlessness and suppressed agitation, of brooding silences and vague dissatisfactions, not quite expressed even to themselves, which emerge under the careful scrutiny of the artist, explored with a compassionate irony and sometimes, a sly, but not unsympathetic humour.

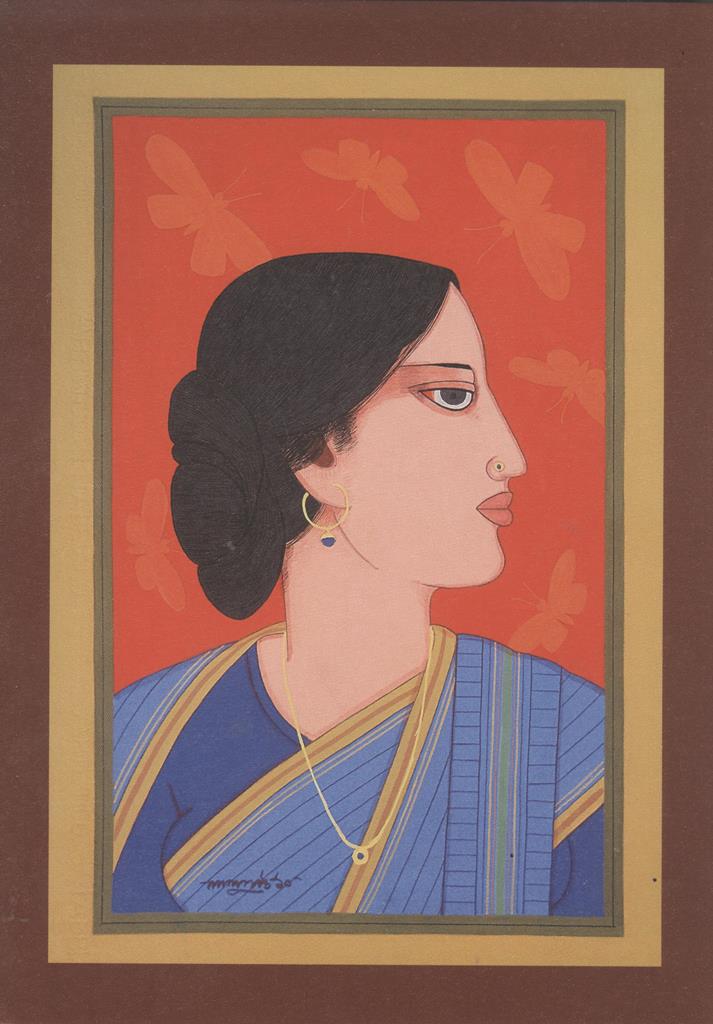

Lives, contained by lines and contours, sometimes threatening to burst free, and figures that dominate the ground of the image, are painted against a flat, solid surface in primary colours, on grainy textured rice paper which offers just a few possibilities away from the deliberate lack of visual depth which is maintained in all the artist’s works. Lalu Prasad Shaw’s chosen medium of tempera links him with some of the oldest traditions of mural painting, Rajasthani and Mughal miniatures, the vivid visual arts of rural West Bengal, as well as the traditional Kalighat pata, with its slices of Calcutta life, hints of social satire and commentary. There was also the cluster of paintings referred to as the ‘Lucknow Bird Paintings’, a series of bird studies commissioned by officers of the East India Company, which had a major role to play in the evolution of his style. At Kala Bhavana, where Lalu Prasad Shaw taught, students reproduced these paintings as part of the academic requirement. For Lalu, they were singular in their use of colour, and clarity of form, elements that he began to pursue in his painting. But instead of keeping with tradition, he used his mastery over the medium and superb draftsmanship, to pursue a gently iconoclastic exploration of his known world.

Before tempera, there was the predictable foundation of an academic training, where Lalu Prasad Shaw did not linger. In the early ’60’s, he commented that ‘… I tried to unlearn all that I was taught as the norms of academic art.” In the pursuit of a medium to express this restlessness, he immersed himself in the abstractions and geometry of printmaking from 1966 to 1973. He emerged as one of the foremost printmakers in the country.

The technique of tempera, which involves using a water -soluble medium, such as egg yolk, the glue from tamarind seeds or gelatin, to apply mineral and plant based pigments, learnt early in his career from one of his teachers, Ajit Gupta, became his chosen medium later for his figurative expressions. It was one as different from printmaking as could be imagined, but peculiarly suited to the distinctive style that he would develop for himself. For the artist there was a consensus in his vision, whether in printmaking or figurative painting: ” …my prints and paintings,” he said, “reflect the same penchant for experimentation with form and space, image and ground relationship, harmony and balance.”

And it is this exploration of form and space, image and ground, harmony and balance that he refined to a pitch in his studies of people. By the ’80’s, the solitary, reflecting figure begins to emerge in his works, in works like ‘Ashalata’, ‘Thinking’ (1984), and ‘The Dreamer’ (1986), although there is some prefiguring of his mature style quite early, in works such as ‘Azaan’ (1954).

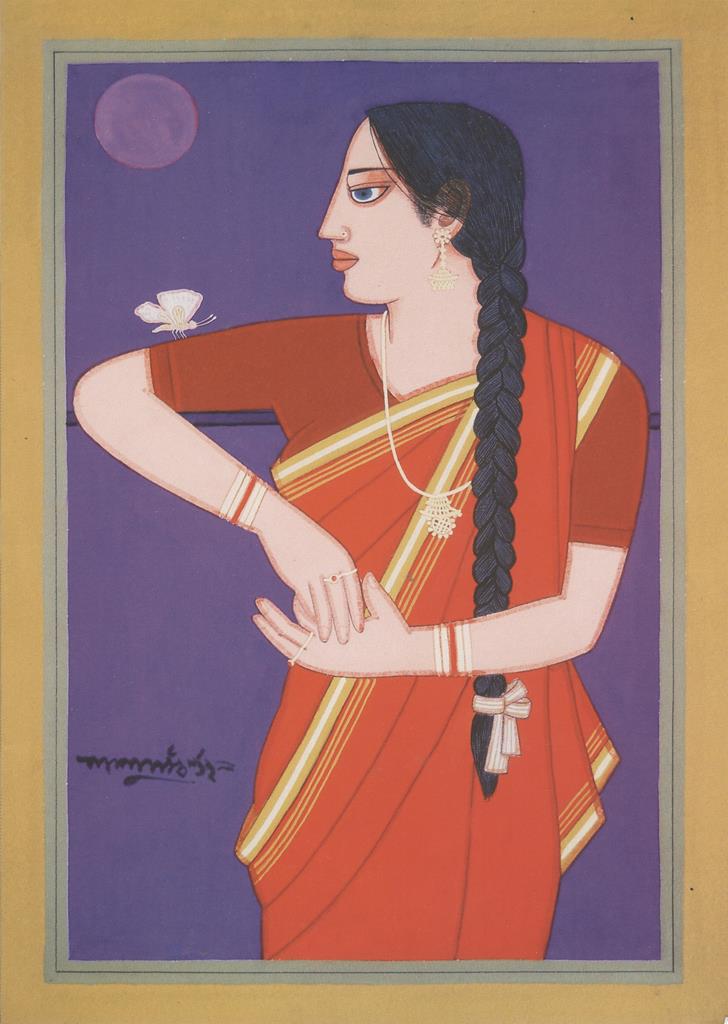

The figures – of solitary women; men; young girls; old aunts; the quintessential dhoti clad Babu; couples trapped in their lonely musings – dominate the foreground, against a luminous, spare, flat background of unspoken anticipation. His people appear to live in a world other than the one they inhabit, one that holds their attention even while they negotiate their way through everyday realities. In the series ‘Waiting’, women in various languid poses stand, sit, stare, groom their lustrous locks, waiting, but for whom, or what? There is a lexicon of imagery being referred to here, of the Indian miniature tradition, where a woman waits for her lover, the entire painting permeated with her yearning, or engages in an elaborate ritual of grooming herself. But Lalu’s women appear to have been waiting endlessly, trapped in a dream world, for a promised or hoped for event that has never occurred. A waiting so long drawn out that the blooms from a vase of flowers have wilted and fallen, but nothing has changed. The eyes are particularly beautiful, elongated, deep, but they evade us, and slide away every time we try to engage them directly.

There is a delicate, allusive quality to his works, where mood is suggested and evoked through the twist of a wrist, the turn of a head, the vulnerable quality of the exposed nape of a neck. There are hints of dreams and desires, but the exteriors are so composed, we never fully know or fathom them- the “whispering dramas” that K.G.Subramanyan spoke of about the artist’s prints are tangibly present in his painted works, expressed with a finely calibrated reticence.

The Bengali babu, posturing his way through the streets and life, is a victim of the artist’s sharp eye and gentle satire. Effete, self important, submerged in a world of his own, seemingly unaware of the ridiculous figure he cuts, he sniffs flowers, smokes, and wanders through life, an umbrella perpetually slung over an arm.

The artist uses colour with great sophistication, the luminosity of tempera uniquely suited to his depictions of silent, solitary people, communicating more than they intended to. Great, solid blocks of vibrant colour form the background to his images, and fearless shades of yellow, red, green and blue and smooth deep browns describe his figures.

There is a subtle exploration of sexuality drawn out in the postures of waiting women and a few background objects charged with significance. Coloured moons- blue, mossy green, a dried blood red – often ride a dream -like night sky, where a woman waits on a balcony; apples are offered with face averted, to the disjointed head of a man; pierced apples appear beside dislocated, trophy like heads; bananas are devoured with unseemly haste, and faces assume a mask like quality. A woman gazes into the distance, elegant, poised, but there is a finger hooked suggestively into the edge of her sari. The artist, with a bare minimum of precisely chosen images draws out the yawning, empty spaces between couples, the repressed sexuality and the stifling boredom of their existence. “Soulmates” is approached with a deep irony – the partner is a decapitated trophy, held on the palm of the hand, subjected to a scrutiny that is at once searching and distant.

Lalu Prasad Shaw’s lines – smooth, taut and stretched – describe these lives; at times they become flabby, irregular and seem to move without coherence, mapping out the inner landscapes of the people they circumscribe, as in ‘Lady Eating Banana (1995). One can only marvel at the quality of a line that can rove over a face, exploring an enormous range of human physiognomy in effortless, fluid movements. The curve of a skull, the droop of a chin, lips that can be fleshy, sensual, or prim, eyes, noses that practically speak are all described with the greatest economy and accuracy.

Often, mask like faces appear on the edge of a work, dislocated from their bodies, an image that runs deep in the artist’s mind. Some earlier works have the staring quality of masks, such as ‘Bholababu’ (1987), ‘Mask’ (1987) and, in a 1997 drawing, there is a definite mask fixed on a woman’s face. Assumed deliberately, the mask intends to deceive the observer and the bystander; but sometimes the it consumes the persona of the wearer, leaving them with no identity except the one assumed, from which there is no escape. Entire worlds lie in the hinterlands of the images; dreamscapes full of thoughts and desires even the people themselves may not be conscious of possessing. But the artist is discreetly privy to them all, and translates them, making them public with a fine sensitivity that somehow avoids a betrayal of trust. His portraits extend beyond mere types, and his whispering dramas penetrate all our lives.