The overwhelming diversity of expression in aesthetics and form in Indian craft comes from centuries of responses to the cultural, utilitarian, sacred, ritual, historic and personal significance of objects. Crafts persons are often highly skilled masters, inheritors of ancient and sophisticated traditions. As a fast paced world edges out the cultural context in which many of these arts were founded, four Master craftsmen share their changed perspectives and their determination to keep their skills alive.

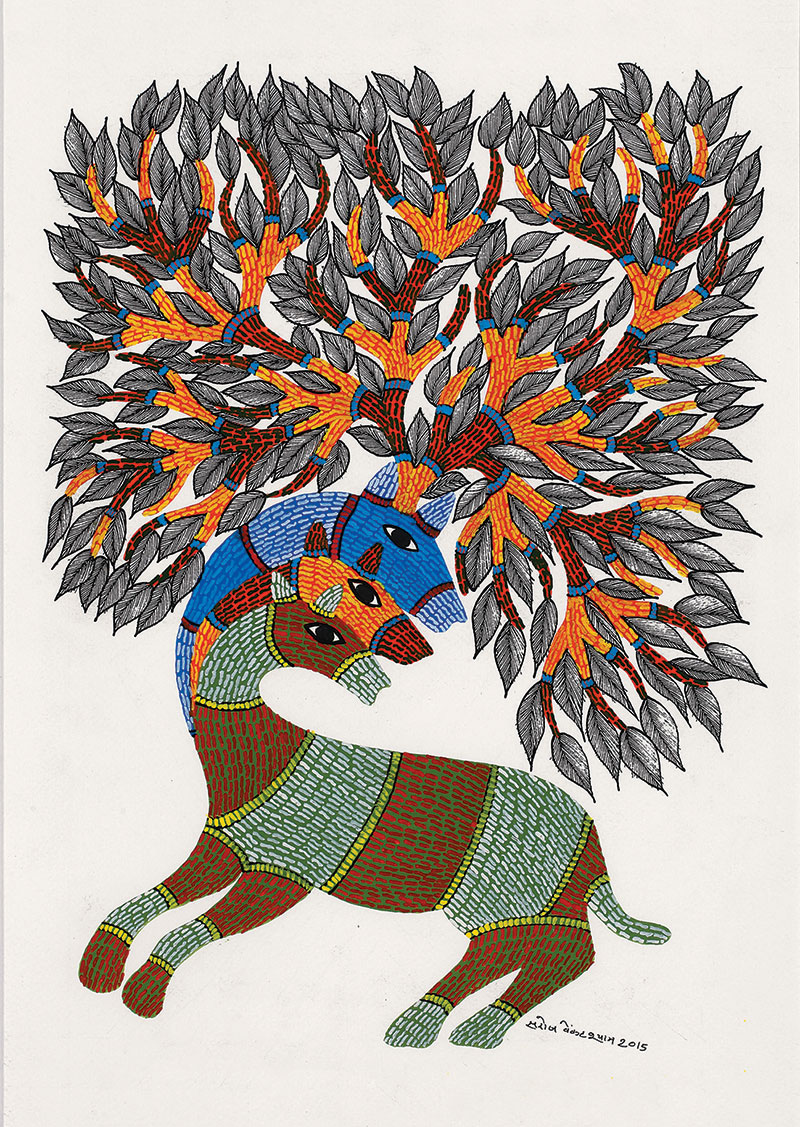

Venkat Raman Singh Shyam, Contemporary Gond Artist

How long does it take to create a tradition? Thirty years ago, Gond art as we know it today did not exist. The traditional stories of creation and nature, painted in natural pigments on the walls of Gond huts in the remote villages of eastern Madhya Pradesh found their way to international recognition and acclaim through the works of one man –Jangarh Singh Shyam. In 1981, the 17 year-old Jangarh was taken to Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal, by the artist J.Swaminathan. Here, the Gond bard drew on a long tradition of his tribe’s storytelling to express himself in various media. His mastery over the use of pointillist dots and fine lines used to express images from folklore and the ancient forests of central India catapulted him to international fame after an exhibition at the Pompidou Centre, Paris and drew comparison with Australian aboriginal art. Jangarh’s life and artistic genius ended abruptly, tragically in 2001, in Japan. But in two decades he had managed to inspire a whole generation of young artists, encouraging them to paint –often with him –and explore their creativity. Quite unwittingly, he had created a style: Jangarh Kalam.

Venkat Raman Singh Shyam, his nephew, then eight years old, was one of the many young people who Jangarh introduced to the world of art. By 1986, he had moved to Delhi to join his uncle, and paint. Staying close to traditional sources of artistic inspiration, Venkat Raman painted, and continues to paint fables, nature, the Creation myth and the tree of life, using natural pigments.

The original paintings were executed on walls of huts plastered with cow dung and lime and a mixture of clay, chaff and water. Local deities, animal and scenes from the nearby forests, the inspiration for the paintings on these walls many seem a long way off from Venkat Raman’s life-sized, fibrecast ‘Elephant Parade’, painted with the story of the ‘flying elephant’ that sold for 25,000 pounds at a charity auction in London –but the sources of the tradition remain the same. Venkat Raman won the state award in 2002, and the Samskriti Award in Calcutta. He will be exhibiting in Virginia, in August 2015and in Melbourne later in the year. His book, ‘Finding My Way’ is due to be published in 2016. He is one of a new generation of artists who have carried Gond art into the 21st century.

Sriramulu and Lalitha Shinde, Master Puppet Artists

On a late autumn evening several years ago, quite by accident, I wandered into an open-air performance of tholu bommalata, the ancient art of shadow puppetry from Andhra Pradesh. I ended up riveted, not moving from my makeshift seat until the show concluded in early hours of the morning. Behind a 12-foot screen of stretched white cloth backlit by hissing petromax lamps, dramatic episodes from the life of Rama, the hero-king of the epic Ramayana, Lakshmana, his faithful brother, Hanuman, the intrepid monkey-god and Sita, Rama’s queen unfolded through the night, the main narrative artfully interspersed with enough local gossip picked up by the puppeteers to keep the audience helpless with laughter at regular intervals. Below the level of the rough stage set up under the stars was a family of puppeteers and musicians who manipulated the leather puppets, sang, accompanied themselves on the harmonium, mridangam and cymbals, controlled the light cast by the lamps and kept up a seamless, highly engaging narrative. It was one of the richest and most skillfully executed artistic performances that I had ever seen, conducted with the minimum of props. I am still haunted by the beauty of the performance, a world of shadow, light and skillful narration. The family of artists had travelled from Nimalla Kunta, a village in Andhra Pradesh, where the art of leather puppetry has been practiced exclusively for over two centuries by a community who migrated from Maharashtra, and thrived under the patronage of the rulers of the fabled Vijayanagar Empire. Through the season, they would travel and perform in village after village, setting up their stage in the open air, and attracting an audience by word of mouth.

Sriramulu Shinde and his wife Lalitha belong to one of the remaining 30 families who continue to keep this tradition alive. To understand the beauty and intensity of these narrative performances, one has to go backstage, into the lives of these artists, lives that are inseparable from their craft. With a National Award to his credit the Government of India has recognized Sriramulu as a Master Craftsman. His travelling companions are all members of his family, making up a troupe of a dozen people, four of whom manage the puppets, four provide the music and the other two are stage managers. Lalitha, his wife, comes from a family of renowned puppeteers, her father a recognized master of the craft. Sriramulu seems unperturbed by the 21st century; his voice rises higher when he begins to describe how they once travelled in caravans of bullock carts across the countryside to villages, where they approached wealthy landowners and farmers, and would set up a series of performances –he speaks with so much passion, it is clear that, for him, life and his art are one.

Sriramulu describes how the puppets are crafted from buffalo or goat hide, soaked in hot water to remove hairs, then washed in flowing water, cut into sections and stretched and mounted on bamboo frames to dry in the sun. They then need to be treated: pounded, oiled and burnished before the preliminary outlines can be drawn, with a needle. The sharpened bamboo pens he and his family use are dipped in black ink made from soot, and used to draw the outlines of bold figures: Rama; Sita; Hanuman, the monkey-god; Ravana –all instantly recognizable characters from the Ramayana. Once the outlines of the body parts are cut out, they are articulated with thick twine and fixed onto bamboo supports. The skill of the artist lies in the intricacy of the patterns of holes that are punched out in the leather to depict costumes, ornaments and regalia that add depth to the backlit figures on stage. This family of crafts persons uses a combination of natural and chemical colours to decorate the figures, some of them up to 7ft in height, painted on both sides of the leather to give an intensity, not unlike stained glass, to the colours when lit up on stage.

The stories they tell are sacred, drawn from the Ramayana or Mahabharata, the characters entirely real to the narrator; he and his family, Sriramulu explains, begin every performance with a prayer to Hanuman, Gannamma Devi, a local goddess and to Balaji. In the integrated community of a village, a typical performance begins at 9p.m., and the entire Ramayana, narrated in Telugu, is played out and ends at about 2a.m. Overseas performances, Sriramulu points out, tend to be scaled down to about 45 minutes, with simultaneous translations of the narrative. Tholu bommalata artists, like many traditional performing artists, face their biggest challenge from television. In a world of fast paced, slick entertainment, there are not too many people who have the patience to sit through a performance that lasts a whole night. Many of them now paint decorative objects like lampshades and mini puppets in an attempt to engage new markets and keep their art alive. But for a Master craftsman like, Sriramulu his pride in his tradition shows in his matter of fact accounts of successful performances in Germany, Argentina, Budapest and Israel, with a visit scheduled to Russia in September. He is confident that his son and daughter, who help out with the shows, will carry on being practitioners of this art.

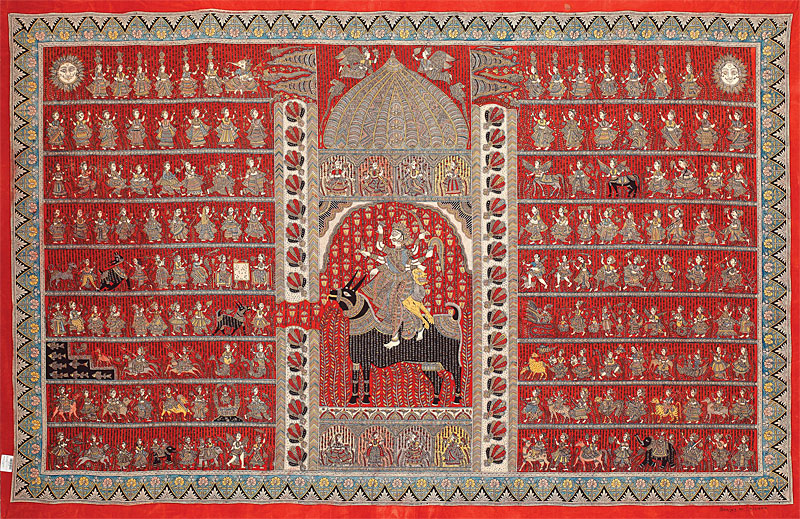

Manubhai Sitara Chunnilal, Narrative Scroll Painter

Manubhai Sitara Chunnilal has been painting for most of his 66 years. His family, who are Devi Pujaks, trace their association with the art of painting ritual cloth back three centuries, which is about as far back as the tradition goes. The narrative cloth paintings in their original context were improvised shrines, made by communities of people who were banned from entering temples. They are also ritual cloths, offered as thanksgiving. There are just five families left in Ahmedabad who continue to produce these painted offerings of thanksgiving that are placed behind the idol in a temple for favours and blessings received from the Mother Goddess. Manubhai, who was honoured with the ‘Shilp Guru’ award in 2009, explains that the traditional narrative cloths used just two colours on a ground of white: red and black, symbolic of the creative life force of the Mother Goddess and black the dark forces of creation. The central figure is always the Mother Goddess, who dominates the composition in one of her many forms: Malleri Mata; Vahanvati Mata; Durga Mata; Vishat Mata and so on, surrounded by a host of other characters from mythology, and her worshippers; there are multiple narratives on separate registers, bound by strongly framed borders.

The artists work on white cotton cloth, with needs to be soaked in water over two days to de-starch it, then treated with myrobalan powder and dried. Manubhai still draws an entire composition by hand, using a bamboo stylus, although he points out there are families now that use blocks to print the cloth instead. The colours are filled in by almost all the members of the family in a technique quite similar to kalamkari painting from Andhra Pradesh. A large Mata ni Pachedi could take up to 6 months to complete, while the smaller ones take about 1½ months of effort. Mata ni Pachedi or Mata ni Chodarva is offered to the Goddess twice a year, at the festival of Navratri and again in the summer months. The old ritual cloths are stored in an earthen pot in the temple, and finally consigned to a river.

Everyone in Manubhai’s extraordinarily talented family is involved in painting on cloth –his two sons, his daughter, daughters-in-law and his wife, who is an award-winning artist herself. With an eye on new markets, to keep the tradition alive, they have moved away from the limited palette of maroon and black made from oxidized iron and palm sugar, and experimented with turmeric, henna and indigo to create a more varied colour scheme. These small concessions to changing tastes turn these narrative scrolls into decorative hangings that would make dramatic centerpieces in urban homes.

Madhukar Gowai, Bidriware Artist

Madhukar Gowai inherited the skills of a bidriware craftsman under rather unusual circumstances. The art of etching intricate patterns on the surface of zinc-copper alloy objects and filling in the channels with fine silver wires, or sheet silver dates back to the 13th century, when Persian craftsmen travelled to India at the invitation of the Bahamani sultans of Bidar, and established a tradition in the North Karnataka town of Bidar that gave its name to the craft. When Madhukar was a young boy, his father passed away, and he was taken into care at a convent in Aurangabad, where a nun who was interested in the preservation of local crafts introduced him to Mohammed Hussain, a master craftsman, who was to become his guru. Madhukar was introduced to a tradition that, with its delicate floral work, intricate geometric patterns, sinuous vines and creepers and calligraphic arabesques on paan boxes, bowls, hookah bases, ceremonial salvers and platters had enjoyed royal patronage from the time of the Bahamani Sultans to the Nizams of Hyderabad. Exquisitely worked pieces are on display in museums across the world, and bidriware made its way to Europe in the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Paris Exposition of 1855.

Contemporary bidriware, already modern when it was first invented with its classic, clean lines and dual colour tone, is made in much the same way that it has been for centuries. First the pieces are cast, using the cire perdue (lost wax) process. The zinc alloy of the base is chemically darkened –although the original works crafted in Bidar credited the mineral rich soil of the region for the exceptionally dark colour. Once the surface is etched out with a design using a sharp steel marker, fine silver wire is hammered into the grooves or, for larger areas, the design is cut out of a sheet of hammered silver and embedded into the base. Finally, the surface is burnished for a beautiful contrast and clear outlines of silver set seamlessly in black. Madhukar is a Master craftsman who still works some of the old designs he inherited from his teacher, in addition to creating modern designs of his own. His son, Vijay Gowai –in fact the entire family –are involved in the process. Mukesh, one of the sons does the casting; both brothers’ wives, as well as their sister handle different stages of creating a piece of bidriware. With an eye to modern tastes, Madhukar, who dedicates his attention to design, is experimenting with jewellery –earrings, necklaces and other objects that might find buyers. Without the traditional patronage of the moneyed upper classes and royalty that supported this craft, the biggest challenge that this family of crafts persons faces –like so many others across the country –is poor marketing and

our master craftsmen, all demonstrating the resilience of their respective crafts; rooted in tradition, but capable of and willing to adapt to suit changed markets and–and their respect for their own place in a long line of masters who have refined and passed down skills that are too precious to be lost, so their determination to carry the traditions forward. So long as there are audiences and patrons, craft will continue to re-invent itself.

This article was published in the Taj Magazine

Image Courtesy: The Taj Magazine