The 10th century gourmet and bon vivant, Chalukyan King Somesvara III, waxes eloquent on the subject of food, in 268 verses of his work, Manasollasa. He expounds on roasts, grills, spit roasting, and the etiquette of eating. Flavours and cooking aromas seep through the centuries in the descriptions of pork balls with ginger, coriander, asofoetida and black cumin; marinades of yoghurt, sugar and filaments of citron flowers; pickles; sherbets of tamarind and pomegranate that sound so much like modern, palate cleansing sorbets. Exotic ingredients like coconut honey, from the sap of palm trees are bought and traded by merchants from China and Yemen. Pool-water in springtime, rainwater in autumn: the source of drinking water changes with the seasons. Instructions on how to dress pork, and remove the notoriously sharp bristles of the wild boar are detailed – smear with mud, and burn in a grass fire, a technique which my husband recalls, was still used by the wild boar loving Kodavas, in his childhood.

A few centuries later, we have the classic Supa Sashtra, of Mangarasa, written in verse, on palm leaf manuscripts, unusually, for housewives. The strong Jain influence of the Karnataka region, from where this book emerged, is reflected in the vegetarian recipes for curries, juices, puddings and snacks. Supa, the Sanskrit word for broth, or soup, extends it’s meaning to the ‘Science of Cooking’ in the title of the book, a work to be found in exclusive bookstores devoted to rare culinary books around the world. Indians, it appears, always knew and loved their food.

Indian cuisine, if you can use such a general term for what is an enormous and varied inheritance, records vast sweeps of history. Recipes for some of our favourite foods carry the stamp of the thundering hooves of conquering armies of Central Asian horsemen, whom we know as the Mughals; of dhow-borne Arabs, who traded for centuries, sailing on the monsoon winds between the coast of Africa and the Gulf, settling on the palm fringed shores of the Malabar coast. Of Europeans – the Portuguese, who added chillis, potatoes and cashews to our cuisine; the Dutch, French, and British, who came to trade in spices, and stayed on to rule. With Jewish and Armenian traders, Zoroastrians fleeing Persia, Chettiars trading with Burma and the Far East, came unusual and exotic ingredients and flavours, which were soon absorbed, typically Indian fashion, into the way the nation ate.

An ancient and sophisticated system of understanding and cooking food already existed before any of them arrived – Ayurveda. The Charaka Samhita goes back to the 5th century. and has been around at least as long as Apicius’ collection of Roman recipes, said to be the world’s first cookbook. Food writing has existed for thousands of years in the subcontinent. Descriptions of food, the feasts of kings, recipes and instructions on how to cook various delicacies are scattered across the centuries in texts, literature and the accounts of travellers.

By the 12th century, the homesick Mongol invaders had begun to import cooks from Samarkand and Persia and very soon, the influence of their food began to be seen at court. In the 15th century, Ghiyas ud din Khilji, the hedonistic Sultan of the eternally romantic kingdom of Mandu, decided to skip the arduous details of kingship, and devote himself entirely to food, drink and women. For today’s epicures, more than five hundred years removed from him, a beautiful manuscript in Persian, the Nimat Namah -The Book of Recipes– with exquisite illustrations, survives from his connoisseurship.

After the Emperor Babur’s famous lament about India, that there were “no grapes, musk melons or first -rate fruits, no ice, no cold water, no good bread or cooked food in the bazaars” the Mughals settled down quite happily to the delights of Hindustan. While the Imperial kitchens lumbered across the Indian countryside whenever the Emperor travelled, on the backs of 50 camels, 200 coolies, complete with china and specialized cooks, under armed escort, the Emperors busied themselves importing the most talented of Persian, Turkish and Central Asian cooks, and planting gardens and orchards. Their passion for food resulted in one of the word’s greatest culinary traditions. Almonds, pistachios, saffron, peaches, perfumed dishes and sophisticated food spread through Royal India across Hyderabad, Lucknow, Murshidabad and Rampur in a great wave, absorbing Indian flavours along the way.

From the court of the Emperor Akbar, comes the Ain-I-Akbari, a gazetteer, with a section containing over fifty recipes, reflecting the tastes of the era. Ice was shipped down the Ganges, wines were imported especially for the lovely Jahanara Begum, and iced summer desserts were the craze. Ibn Batuta, the traveller, describes banquets of forty courses. The British, newly arrived in India, tucked into these banquets enthusiastically at the court of the Emperor Jehangir, and very soon replaced the Mughals at their own table.

India had a new hybrid cuisine –that of British India. The titles of the cookbooks of the era say it all: What to Tell the Cook, or the Native Cook’s Assistant; ‘Chota Sahib’ Camp Recipes for Camp People; Indian Recipes for English Tables, and the famous Indian Housekeeper and Cook, by Flora Annie Steele and Grace Gardiner. As the British mems struggled with stringy, country chickens, alien vegetables and befuddled cooks, a whole new cuisine of club, mess and dak bungalow emerged.

To get to food writing and the cookbook, as we know it, you have to leapfrog over the centuries, to the mid-19th and into the early 20th century. The glories of Persia, the Mughal heritage, alternately expanded, condensed, and refined in the Royal kitchens of Central India, Awadh and the Deccan, are distilled into Cooking Delights of the Maharajas. This is a book created by a royal connoisseur and perfectionist, His Highness, Digvijay Singh of Sailana, in Madhya Pradesh. A renowned gastronome and aesthete, the recipes, culled from Sanskrit, Urdu and Persian manuscripts over decades, from all over Princely India, are refined and presented. With dishes like Kalia Razala, a delicacy from one of the Begums of Bhopal –mutton cooked in a simple cluster of spices in a sealed pot; Chui Mui ke Kofte, Garlic Pulao, Mutton Halwa and Sabat Khargosh (not for the faint hearted!), this book harks back to an era when gastronomy was a highly refined art, and Royals like The Nizam of Hyderabad, Awadh, the Nepalese royals, Jhabua, all vied with each other to keep the most excellent tables, and patronized chefs of the greatest talent and imagination, who outdid each other with incredible dishes.

Tracing this legacy is Jiggs Kalra’s Cooking with Indian Masters. Working with a possé of some of the country’s finest chefs, like Mohammed Imtiaz Qureshi, Todar Mal and Arvind Saraswat, he draws out lively salads of cold Indian meats, classic tandoor and kebabs, exploring the world of handi, khadai dum pukht, tawa and much more. An excellent glossary of cooking terms helps; the range of ideas is extensive, and perfectly adapted to home cooking.

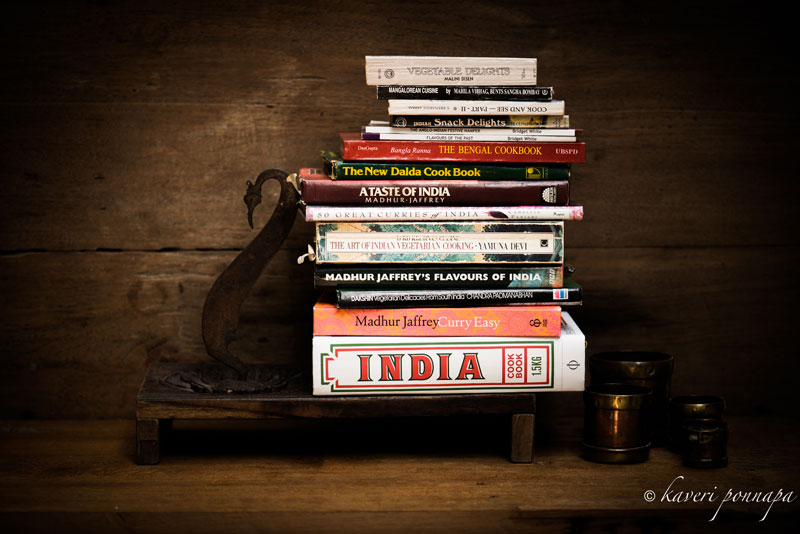

British India is best represented in E.P, Veeraswamy, who was Edward Palmer, and not Veeraswamy at all. He founded the most famous Indian restaurant ever, in 1926,which was haunted by the rich and famous. He wrote a quaint, Raj flavoured cookbook, full of words like Pah- Phads and Tyre (curd!). Veeraswamy’s, the only British restaurant to feature in National Geographic’s 10 Best Destinations in the World, is today associated with the peerless Camillia Panjabi, who gave us the classic Indian cookbook, 50 Great Curries of India. Informed, meticulously researched, exploring the rich regional cuisines of India, it had sold 1million copies by 2007. If you own only Indian cookbook, it has to be this.

Having grown up in an assortment of cantonment towns, the world of Jennifer Brennan’s Curries and Bugles, is a familiar one. It’s a book I reviewed 18 years ago, and as far as I know, remains unique, as a modern cookbook of the Raj. Sheer, unabashed nostalgia and recipes evocative of a bygone era, it is full of dak– bungalows, picnics, shikars, garden parties, clubs, gymkhanas and mess dinners. The food is typical –Steamroller Chicken; Byculla Club Soufflé, and old- fashioned recipes for Punch and ‘Burra Pegs’. The Viceroys of India lived it up in grand style, employing French chefs, who sometimes ran away and set up their own restaurants. In pre-independence India, imported chefs catered to Western tastes. But there were some unusual stories. While holidaying at the Taj Exotica in Goa, dining at a restaurant named Miguel Arcanjo, I discovered the world of one India’s legendary chefs, and his extraordinary story. Masci, The Man Behind The Legend, is the incredible story of a penniless kitchen boy, who went from cleaning 20 dozen chickens at a time, accounting for every liver and gizzard, to becoming Chef de Cuisine of the Taj Mahal Hotel, Mumbai, cooking for heads of state and Royalty. The heart-warming, inspiring, story is woven in with some of his favourite recipes, scribbled down on paper napkins and doilies over the decades, many of them, happily, from his native Goa.

A great number of Indian cookbooks are at best modest presentations, written by housewives, often quite shabbily printed, the recipes certainly not haute cuisine, but invaluable in their unique way. Through them, one enters the private world of regional cuisine, and delicious home cooking. These women, custodians of tradition, bring to their dishes generations of experience. While cookbook snobs spurn them, I have found them to be a storehouse of information, and superb recipes. And there is the added sense of excitement, when unassuming texts yield great treasures for the table. Meenakshi Ammal’s Cook and See celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 2001. Updated, without the earlier, fascinating, but despair-inducing measurements of 5/8ths of an ollock, palams and stone vessels (I still haven’t figured out that one!), this is full of traditional tiffins, salads, pachadis, chutneys and more from vegetarian Tamil cuisine.

A much-used book on my shelf is Malini Bisen’s Vegetable Delight’s. Every imaginable vegetable is put into alphabetical marching order by Mrs. Bisen, so you are never at a loss, staring at local varieties, wondering how to cook them. I also love the sound advice she offers, gems such as: ” Have a genuine liking for your guests, or do not invite them;” urging a hostess to engage her guests in light and amusing conversation. Or investing in a pressure cooker, instead of a cook, as he will eat too much, and throw your budget!

Ummi Abdulla’s is a much gentler voice, but the unique flavours of her Mapilah ancestry –her Fish Biryani, Erachi Porichathu, and Erachi Choru are good enough to merit being on the menu of an upscale restaurant. From further north, up the same coastline comes a book simply packed with fabulous recipes –Saraswat Cookery, by Shalini Nadkarni, in which pomfret, mussels, oysters and crabs, cooked so differently from Malabar. The fresh flavours of kokum, peppercorns and coconut permeate even fresher catches; the lowly mackerel is steamed, baked in turmeric leaves, stuffed, roasted and pickled into mouthwatering creations.

Several thousand kilometers removed from the Saraswats is another community of fish-loving gourmands, the Bengalis. Meenakshi Das Gupta, alias Kewpie, who was something of a Calcutta institution, started the tiny and quite unique Kewpie’s Kitchen Restaurant. Bengali Ranna is replete with the flavours of Bengal, with recipes for the entire gamut of Bengali delicacies like the spectacular, and incredibly simple Chingri Daab, often presented at my table.

In a country full of vegetarians, and a multitude of cookbooks to choose from, I’d plump for one, single, bulky tome –Lord Krishna’s Cuisine, by Yamuna Devi, alias Joan Campanella. Packed with the freshest of flavours, and unmatched for sheer variety and brilliance, chutneys, dals, and sabjis never looked so attractive and colourful, or tasted so good before. For a dyed in the blood Coorg, I turned pure vegetarian for three whole months, when I first bought this book.

Indian cookery has its share of celebrity writers. Feasts appear to follow in the wake of the legendary, and charismatic, Ismail Merchant. In Passionate Meals, and Indian Cuisine, he conjures up sparkling dishes, like Mustard and Prawn Chive Bites, Spicy Fish Roe, Lobster in Spicy Coconut Sauce. Parsley and dijon mustard figure in what is smart fusion cuisine, before the term was invented. His books are full of anecdotes, peppered with famous names. This is food drama, and his particular combination of the gathering of friends, exotic food, and atmosphere is worthy of a magnificent Merchant-Ivory production.

Madhur Jaffrey, a true original, wields her expertise in my kitchen. Her Ultimate Curry Bible looks set to become a classic and my spice splattered A Taste of India still turns out perfect Kholapuri Mutton and Achari Gohst, with Madhur holding court, like an regal and gracious queen, over the over the smart young set like Anjum Anand and Monisha Baradwaj.

A book full of tender little drawings and, wonderful, surprising food, is My Bombay Kitchen, by Niloufer Ichaporia King. Hers is a modern voice, expressing many unusual ideas. A series of delectable ices, so suitable for our endless Indian summers, created from Campari, rose petals and Angostura Bitters; Cardamom Cake; Andrew’s Goa Curry; Kenya Masala Butter rub shoulders with traditional Parsi fare.

If you consider, that ports on the Indus delta were importing Italian, Greek and Arab wine, and exporting spices, by the 1st century C.E, and tandoor-like clay ovens have been found in Kalibangan, from about 5000 years ago, it’s not surprising that we are likely to have a lot to say about food in this country.

The Indian Epicure was published in Food Lovers Magazine Vol 3 Issue 5 Oct/Nov 09.

Image Credits: Nithin Sagi

Thank you for this treat Kaveri. Somehow I has missed reading this post but totally enthralled now as I read it. Waiting fornyour Coorg cookbook to be in this illustrious list now. Much love.

I am delighted you enjoyed reading this, Sangeeta. Thank you very much for your generous words, and I do hope my book lives upto expectations! Warmest wishes. Kaveri

Kaveri Madam I am very fond of Indian food and if food is weaved so well with its history by you, I am definitely going to connect each dish with its source of origin and enjoy its flavors even more.

I can’t wait to add your book- hopefully you will put one out, to my shelf of cook books. I hope the wait is not inordinately long!

Hello Rahul, thank you for visiting these pages and for your kind words. Much needed encouragement at this moment, when my cookbook is insisting on asserting a will of its own, refusing to stick with any of the strict deadlines that I keep putting down. It is progressing, though, and I hope that the finished product will be worth the wait. In the meanwhile, please keep reading, and I always welcome questions and comments. Best wishes. Kaveri

Oh my God! I chanced upon this article while pondering the question ” which Indian cook book to buy” ( to start cooking post loss of a cook ! ) – and cant believe how beautifully researched and informative this is. I am so happy and relieved that they are written by Indians ( except the British Raj style cooking one) a lot of whom actually live in India ! Not by Rick Stein etc….

And realised also that one cant have just one cookbook. This country offers a lot.

Thank you .

Hello,

I know you must have heard it so many times before but I would love to say it again that I have absolutely fallen in love with your blog. It started with my coorg table and simply flowed here. I am not an expert in cooking nor in literature but I sincerely felt at home in your food and Coorg memories. The choice of words was evocative without the flowery and sweetness overdose. I imagined coorg and somewhere in my mind I travelled it all,tasted it all and loved it all.

I have always liked to read food history and memories of food. Honestly, I read your blog when I am having lunch. I know that it’s a bad habit but your blog whets my appetite;)

I just had a question. Do you have any suggestions for memories and food interconnected books? Something like Madhur Jaffery’s climbing mango trees or bong mom’s cookbook by Sandeepa ?

Thanks, somehow I never had guts of writing to you and today just seemed to be right ( maybe I fooled my guts)

Take care,

Warm regards,

Ashwini

Hello Ashwini, I will never get tired of hearing people say they enjoy my blog and writings, it’s always great to know that a piece of writing has evoked a response in someone else. So go ahead and write in as often as you like! You may enjoy ‘Toast’ by Nigel Slater, although it is rather sad, and ‘The Hour of the Goddess’ by Chitrita Banerji. Do keep reading these pages. Warm wishes.Kaveri

Hello Pratima, my own copy of Malini Bisen’s book is over 20 years old, and in quite a precarious condition. I have not seen any new ones around, so I guess it would be best to hang onto your old one! Kaveri.

I am looking for the cookery book titled – Vegetable Delights by Smt. Malini Bisen. I was told to try it out on amazon.in as it is found in amazon.com. Unfortunately this book is not in the list in amazon.in. I wish I could get this particular book as the one I have is decades old and in tatters. A lot of sentiments attached to this book. 🙁

I wish somebody could help me in finding out where exactly I could buy this from online.