A fruit that has been around for over 20 million years floats hundreds of nautical miles across open seas and when it bumps into a landmass, it sprouts and flourishes. Cocos nucifera –the coconut, its presence recorded in Tamil literature as far back as 100BCE, a possible resident of Mohenjo-Daro; the ‘hobgoblin’ of Portuguese sailors, weird and wonderful because of its two vivid eyes and mouth, sometimes called the tree of life. The coconut is believed to have travelled all the way from Polynesia, to transform the cuisines of most of peninsular South India.

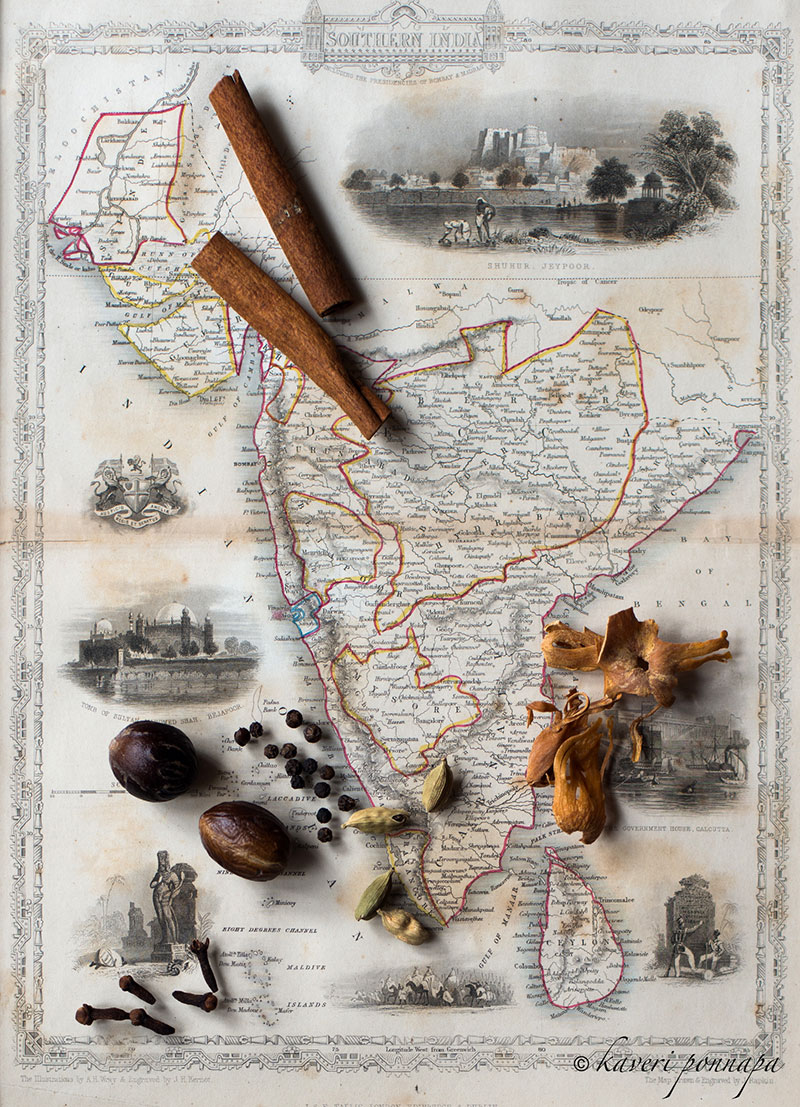

The ancient land that now makes up the four southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with its edges of never-ending shoreline lapped by vast oceans was a cosmopolitan and sophisticated place, accustomed to trading in spices and luxury goods for thousands of years. Its port towns were tremendous crossroads of trade and cultural exchanges, peopled by Greeks, Arabs, Romans, Jews, Egyptians and a dozen other nationalities. Ships plied busily in and out. They came for pepper –priceless and much sought after, the key to the spice trade; for cardamom, ginger and cinnamon; for spikenard, sesame oil and even ghee, which was transported in leather skins to Imperial Rome. The south was wealthy and picturesque. Calicut was full of fabulously rich Mapilah merchants; Cannanore replete with ‘cucumbers, melons, coconut, pepper, ginger and cardamom and other spices’; and Vijayanagar, at present day Hampi, with its orchards of fruit trees, lime and orange trees, parks for hunting, markets overflowing with fruits, left Italian travellers like Nicolo dei Conti and the Portuguese Domingo Paes awestruck.

And food travelled too, mostly with people, sometimes, like the coconut, quite by itself. Many grains like bajra, ragi and jowar, still everyday cereals of the south, migrated from Africa, while the banana, betel leaf, areca nut and sago palm came from South East Asia to establish themselves firmly in the food preferences of the South. Rice, now indispensible in southern cuisines, made its way across the country form the North East relatively late, that is to say, around 1000 BCE.

A quick look at this region, before the Aryan push from the North shatters every myth of the vegetarian South. From exotic meats like iguana, tortoise and peacock, to quail, parakeets, wild boar, venison, beef, hare, fish and prawn –in short everything –was presented at table. Alcohol was brewed from germinated grains and toddy from the sap of the Palmyra palm, both consumed without inhibition or hypocrisy by everyone, including women. Even today, the South surprises, with a deeply entrenched tradition of meat eating populations – Tamil Nadu, Andhra and Kerala emerge as amongst the lowest vegetarian states across the country, while Karnataka reflects its Jain heritage by being the most vegetarian of the southern states.

Thanks to two gourmet kings, who set down descriptions of food in a couple of classic tomes, we can take a virtual tour through the kitchens of royalty, as well as commoners and monks of the times, with vivid accounts of cooking techniques, food, dining etiquette and much more. The Manasollasa -meaning ‘that which refreshes the mind’ – of King Someshwara of Kalayana, in the Bidar district, west of Hyderabad, makes short work of vegetarian fare and luxuriates in descriptions of the preparation of meats. Written over eight hundred years ago, it describes liver carved into the shape of betel nuts, charcoal roasted and fried with spices; spit roasted whole pig; roasted tortoise; brinjals stuffed with ground meat – Manasollasa is specific not just about the cuts of meat, but lingers over the artistry of meat shaped like plums, or amlas. Anticipating the Mughals by several centuries in their love of one kind of food masquerading as another, the cooking of rich southerners was fanciful, indulgent and utterly extravagant. Pepper, turmeric, ginger, cloves, cardamom, tamarind, lime were the signature spices and flavours of the south, with a restricted use of mustard. Pepper was a prized spice for it’s properties as a preservative and, it’s old name, kari, is the likeliest source of the later, curry that became generic for any spiced dish. Roasting, marinating, frying and boiling were all popular cooking techniques, but ancient South India was particularly fond of the barbecue –of ‘hot meat roasted on the point of spits’, whole roast wild boar. A barbeque enthusiast, separated from us by many centuries, quite carried away by a scene of roasting meat goes into poetic ecstasies, describing the dripping fat like drops of rain that fall in a full lake!

Basavaraja, King of Keladi in Western Karnataka, dives into the elaborate and elegant manners for dining current at the time he wrote, in the late 17th –early 18th century. Drinks and rotis to the left, greens and vegetables below rice, which had a special position in the centre; with some regional variations, you would find similar patterns in a banana leaf meal eaten in the South, even today. A man with an eye for detail, Basavaraja endears himself to a food lover with his meticulous description of cooking spaces and utensils, including the classic coconut scraper, now almost extinct in our kitchens. This vegetarian poet-king dwells on the ancient principles of Ayurveda that have influenced deeply the food of the South –of sweet, sour, salty bitter, spicy and astringent, served in that order at a meal. Any meal was concluded elegantly, with scented water to wash the hands, perfumed toothpicks and betel leaves, stuffed with spices and camphor to sweeten the breath. The chewing of betel leaves, originally a southern pastime, drew the attention of many foreign travellers who made copious notes on the leaf. Abdur-Razzak, Ambassador from Samarkand marvelled at its stimulating qualities, comparing it to wine, with the added advantages of being a digestive and breath freshener. He concludes on a somewhat prudish note, declaring that –“delicacy forbids me to expatiate on its invigorating and aphrodisiac qualities”.

A deep respect and passion for food runs through these times, its emotion and poetry captured in literary outpourings. Karnataka is particularly fortunate in a heritage of recorded writings on food, extracts from various writers stretching back a thousand years, compressed into the vegetarian Supa Shastra of Mangarasa, originally published in 1516CE. Rotis of every description; the technique of baking on heated tiles; detailed vegetarian cooking –mixed fried vegetables steamed in turmeric leaves and fried tender bamboo shoots for instance; sweets, exotic, elaborate, perfumed with flower petals and baked on hot coals; many others recognizable- like kesari bath, ladoos and payasams are part of these elaborate writings.

And where are these antique foods now? Sifting through the centuries, familiar, everyday names pop up: idlis, vadas, puris, sandiges, happalas, holiges, kadabus, kajayas and pacchadis, perfected centuries ago, miraculously still here on our plates today. Vegetables heaped up in local markets around the South are much the same as the ones described in the Supa Shastra – colocasia leaves, brinjals, green bananas, amaranthus, a host of leafy greens, yams and tubers.

Rice, which is the mainstay of the South, reached these parts three centuries or more later than the rest of the country. But once established, southerners refined its use to an art form. It was parboiled, sand-roasted and puffed, pounded, steamed, drunk as a gruel and seasoned. Puli-sadam, tangy tamarind rice, chitranna and pongal all date back over a thousand years. Appams and idi-appams go back to the 5th century, while dosas and idlis, which were originally shallow fried –the techniques of fermenting and steaming, thought to have been imported from South East Asia, were yet to arrive –go back almost as long.

Identities and food molded each other. Different groups of people lived in close proximity, often using the same or similar ingredients, accepting some, rejecting others and combining what they chose with imagination, so that what you have is an incredible range of dishes and flavours in a single region. Right next door to the Jain vegetarian kings were the Deccan Sultanates of Golconda and Bijapur, the gateway to the south, later the dominions of the Nizams of Hyderabad, where food reflected the crisscrossing of countless armies, of Persians, Mughals, Turks and Central Asians, of a rich and unabashedly luxurious cuisine; of sheermal and nihari– trotters and tongue cooked patiently through the night- of lukmi; biryanis, mirchi-ka-salan and shahi-tukda. Not quite as familiar with the spices of this region as I would like to be, I asked Mandaar Sukhtankar, Executive Chef of the Park Hyderabad, who has been roaming the by lanes and homes of the city, capturing the complex intermingling of the traditional of Hyderabad, Telengana, Rayalseema and Andhra for the restaurant Aish, and this is what he shared –cinnamon, cardamom, dagadphool (dried lichen), badi laung, khas and cubeb peppers define Hyderabad, which steers away from the fiery tastes of Andhra. Elsewhere in the region, chilli, turmeric, ginger, mustard, fenugreek, coriander, cumin and gongura leaves are the building blocks of flavour.

A southern style of cooking, long erroneously associated with high spice levels is Chettiar. Meenakshi Meyappan, an authority on the food of the Chettiars is emphatic that their food is not fiery hot, but makes use of coriander seeds, cumin, fennel and fenugreek, with peppercorns, and the mild Ramnad chilli. One of her favourites, uppu kari, dry fried mutton made with de-seeded chillis, shallots and gingelly oil bears this out. A lookalike of a 16th century dish that appears in Chettinad is mandi, a vegetarian blend of okra, green chilli, shallots, garlic and tamarind water. Mandi is cooked in water in which rice has been washed, a technique recorded in other parts of the South at least 400 years ago.

On a ravishing sweep of coastline on the western fringes of Karnataka, Bunt, Catholic and Gaud Saraswat Brahmin heritages rub shoulders, each one subtly varying the same principles –a fish curry is given a sour tang with the use of either kokum, tamarind, or raw mango, leading up to very different, equally delicious results. Rice surfaces as delicate neer dosas, eaten with the iconic kozhi gasi or sannas: cushiony, toddy fermented, paired with pork sorpatel. The stewed pork of the coast could not be more different from the pandi curry of the highland Kodavas, who have perfected a cuisine around hunting and farming, with a whole series of inventive, steamed rice puttus and the expert use of a concentrated vinegar from the same family of kokum fruit which is used dried on the coast but in a liquid form here. Barely a couple of hours away from them are the Mapilahs, who brought pattiris and aleesa with them on their journey from the Arabian Peninsula. Kerala’s coast produced some of the most original flavours in a land where the coconut really was king. The surreal, Land of the Lotus Eaters atmosphere of the backwaters produced its own, unique feasts. Rustic toddy shop country style cooking evolved and, in Suriani kitchens, erachi olathiathu (fried beef) and meen vevichathu (fish curry in a mud pot) simmered on wood fires, toddy scented appams and tapioca, yam and breadfruit appeared on the table.

The sea carried influences back and forth. From the other end of the world came the chilli, which in time would become the definitive spice in most Indian cooking. The humble bajji, vegetables dipped in a besan batter and deep -fried, carried to Japan by the Portuguese, became the ethereal tempura. Fish moilee, quintessentially Keralite, drifted in from Malaya, while the Chettiars, who traded extensively across South East Asia brought back star anise to flavor their meat curries, and kavunarisi a sticky black rice made into a sweet at celebrations. Such intricate exchanges and entangled histories leave me wondering about the Protected Designation of Origin status of all these foods. What really belongs where?

So where are these foods from our past headed –feasts of kings, everyday fare of ordinary people, of traders and monks? The histories of migrations, shiploads of spices, travelling foods, identities and the human imagination are all mixed up in dishes that could inspire poets centuries ago and, can still open up a floodgate of memories for us: of soil, water, sky, seasons and familiar tables, where much-loved flavours were created day after day. I suppose in a way it all depends on us: whether we will make space and time in our lives to love these foods with the same passion that went into their creation all those years ago.

The South on a Plate appeared in Food Lovers Magazine, April-May 2012

Image Credits: Nithin Sagi

All Styling: Kaveri Ponnapa

Very nice blog.

very nice blog that you have shared