Leaving behind the elegant sweep of the Venetian harbour and old lighthouse, we follow cobbled lanes winding down narrow streets, all golden stone, overhung with heavy wooden facades and balconies on a quest for the best handmade baklava on the island of Crete.

Our footsteps echo through corridors edged with churches and grand mansions built for Venetian noblemen that stand beside mosques and minarets from later Ottoman rule — thick strands of history running close beside each other at every turn. Kyr Yiorgos Hatziparaskos has lived upstairs from his pastry shop for 60 years, starting his day at 6.30am, and winding up by 9pm. In his mid-eighties, he moves with the careful precision of age. At the wooden tables where he works, though, there is the confidence of seven decades of baklava making visible in his hands as he tosses stretched dough into the air to form a vast, paper-thin dome. It soars upwards, impossibly light, and balloons, before settling gracefully on the work surface. Katerina, his wife, smiles with quiet pride from behind the counter where she sits, as though she is watching this for the first time, instead of the uncounted occasions the identical scene has played out before her eyes over the years.

Kyr Yiorgos Hatziparaskos has lived upstairs from his pastry shop for 60 years, starting his day at 6.30am, and winding up by 9pm. In his mid-eighties, he moves with the careful precision of age. At the wooden tables where he works, though, there is the confidence of seven decades of baklava making visible in his hands as he tosses stretched dough into the air to form a vast, paper-thin dome. It soars upwards, impossibly light, and balloons, before settling gracefully on the work surface. Katerina, his wife, smiles with quiet pride from behind the counter where she sits, as though she is watching this for the first time, instead of the uncounted occasions the identical scene has played out before her eyes over the years.

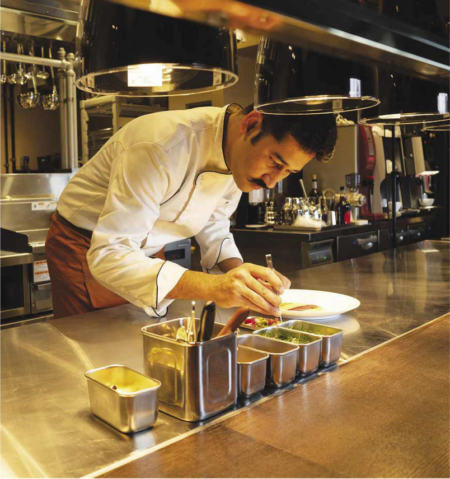

In a high-ceilinged room of this 17th century mansion, the entrance framed by a marble doorway, its walls washed white, sheer sheets of pastry are spread out on the tables, separated by linen burlap to absorb moisture and keep them from sticking. In a back room, Kyr Yiorgos controls the flow of a thin mixture through small perforations in a container directing it onto the surface of a spinning copper pan. The strands of ‘angel hair’ bake within minutes of contact with the hot pan and, in a smooth, practiced movement, he sweeps up the threads that make kataifi. After a lifetime of kneading by hand, Kyr Yiorgos has only recently begun to prepare the dough with mechanical assistance. The fillings embedded within these syrup drenched delicacies are walnuts, almonds and sesame, the limited daily production keeping everything absolutely fresh.

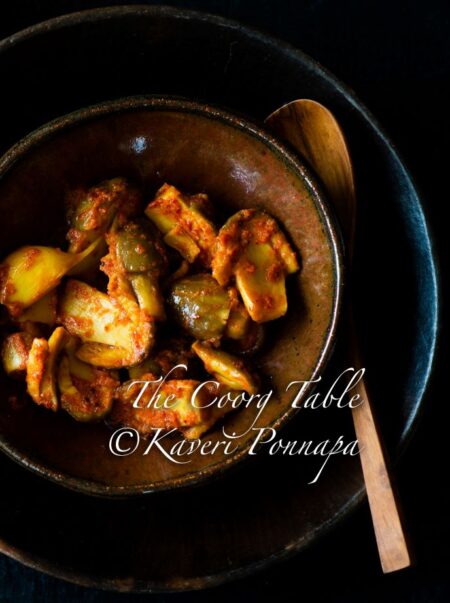

We eat samples from arrangements of baklava that glitter and shine, studded with nuts, sticky with syrup. Layer after layer of pastry turned light and translucent by heat and sweetness, every mouthful is heavenly; the crackle of layers of thin, rich pastry; the drenching sweetness and the crunch of nuts, everything lighter than air, melting away before you can truly have your fill. Luxurious and ephemeral, evoking enough emotion to have been the cause of bitter arguments and quarrels between countries.

Attributed —in its early forms —to the Central Asian nomadic Turks, the name linked by scholars to the Mongolian root word ‘tie up, or ‘pile up’, and most likely refined to its present form in the elaborate kitchens of Ottoman Istanbul, the Greek claim to the ownership of baklava has been toppled in academic research, as well as in the ‘Baklava Wars’ of 2006, when Greek Cypriots presented it as their national sweet, only to be challenged by Turkey, at the European Commission. Turkey, which exports of 5 ½ million dollars-worth of baklava annually, overseen by the Baklava and Dessert Producers Foundation, takes the sweet very seriously. It was quick to move Brussels against the Greek claim, and secured a GI for baklava, putting an end to any argument regarding its origins. The national importance of the sweet is reflected in the annual baklava festival held in Istanbul’s Eminonu Square, and the revival, in 2014, of the historical Baklava Procession in Sultanahmet Square, recreating the Ottoman custom of presenting the janissaries of Istanbul large trays of baklava on the 15th day of Ramzan.

Attributed —in its early forms —to the Central Asian nomadic Turks, the name linked by scholars to the Mongolian root word ‘tie up, or ‘pile up’, and most likely refined to its present form in the elaborate kitchens of Ottoman Istanbul, the Greek claim to the ownership of baklava has been toppled in academic research, as well as in the ‘Baklava Wars’ of 2006, when Greek Cypriots presented it as their national sweet, only to be challenged by Turkey, at the European Commission. Turkey, which exports of 5 ½ million dollars-worth of baklava annually, overseen by the Baklava and Dessert Producers Foundation, takes the sweet very seriously. It was quick to move Brussels against the Greek claim, and secured a GI for baklava, putting an end to any argument regarding its origins. The national importance of the sweet is reflected in the annual baklava festival held in Istanbul’s Eminonu Square, and the revival, in 2014, of the historical Baklava Procession in Sultanahmet Square, recreating the Ottoman custom of presenting the janissaries of Istanbul large trays of baklava on the 15th day of Ramzan.

Turkey may have established its ownership of baklava with international registrations and public announcements, but its cultural significance runs deep across the Middle East and several other Central Asian countries, inextricably entwined with life itself; everywhere it is made, generous quantities of baklava are always present at celebrations, major life events and every significant social occasion. It has taken root across a broad swathe of countries, carried by trade and migration, absorbing local ingredients and nuances, the fillings changing with geographical boundaries, baked in a variety of styles. Here, in Rethymno, Crete —an island captured by the Ottoman Empire, declared an Ottoman province in 1646 and ruled for two and a half centuries from Istanbul —amidst faded walled gardens, mosques, and the remains of Turkish architecture is a legacy of handmade baklava kept alive by a master of the art, ingrained in the life of this ancient town.

It takes a lifetime to gain the expertise required to bake these airy sheets of pastry. For Kyr Yiorgos, it began with a decade long apprenticeship as a young boy, working in a business owned by relatives before he set out on his own. Amidst the trays lined with kataifi, its fine shreds and twists soaked in syrup, bird’s nests and layers of traditional baklava, he demonstrates how to knead, stretch, shred and chop with patience and enthusiasm, his brows and arms covered with a dusting of flour. Paraskevas, his son, works beside him; quietly spoken, an engineer by training, he will continue the family business, facing the challenges of changing tastes and the easy availability of mass-produced alternatives.

Kyr Yiorgos, his eyes sparkling with life, surprises us when he shares his lifelong passion for Hindi cinema and film music of the ’50’s, ’60’s and ’70’s. We have an extended conversation about favourites, and promise to send him a selection when we return home —which we do, picturing the songs from Guru Dutt films and Sholay filtering down to mingle with the glittering sweets that have travelled across so many borders, and captivated people across cultures. What would the ‘Baklava Wars’ matter to an artist who continues to pursue his craft with so much passion and dedication?

By: Kaveri Ponnapa

Images Courtesy: K.P.Ponnapa

This was published in UpperCrust Magazine, 3rd Quarter 2019