Part of the story of how Karavalli went from being something of an anomaly when it opened in 1990, to becoming the most famous restaurant in the world serving the traditional food of the south western coast of India lies in the bowl of Allapuzha Meen Curry placed before me. The bright red colour is deceptive —the flavours are tart, fresh rather than fiery, the tender cubes of seer fish immersed in a smooth sauce of spice, coconut and raw mango, with refreshing hints of ginger. Instead of the usual red rice, there are delicate, moist neer dosas, perfect for scooping up pieces of fish and soaking up the sauce at the same time. Seated in the now familiar surroundings of a Mangalorean-style home, all dark wood and heavy chairs offset by a lush, tropical outdoor space, I have eaten this curry dozens of times over two decades, but still look forward to it, enthusiasm undiminished. No matter how many times you come back to it, the flavours remain true. Oggaraneda Aritha Pundi, the tongue twister of a name for the tiny rice steamed dumplings coated in a crunchy crust of popped mustard seeds, urad dal, curry leaves and a dash of sugar that served as starters have been consumed, and the rest of my choices are arranged on a thali before me. There’s Chevod Balchao, generous chunks of extremely fresh lobster steeped in Goan vinegar and pickling spices; Southekai Pachhadi; Enne Badnekai and Maavinakai Mensukkai to get through. More about these presently. It’s going to be a long afternoon, but a meal at Karavalli cannot be hurried. After all, they have taken their time mastering every one of the dishes, everything slow-cooked, often over a wood fire, in hand ground spice pastes.![]()

“The first 10-15 years, there was barely any change in the menu. 15 years were dedicated to learning,” says Chef Naren Thimmaiah with breath-taking simplicity and confidence. “The next 10 years ushered in some measured change”. At a time when food trends in the country rise, travel across the culinary firmament with meteoric speed, only to disappear just as quickly, and chefs everywhere are hard pressed to hold the wavering attention of a clientele pressing for innovation, this single statement says everything about what you can expect at Karavalli.

Ahead of its times by at least a couple of decades, it was the genius of the legendary Camellia Panjabi that inspired the creation of this restaurant. The long sweep of coastline that begins in Goa and stretches across Karnataka, all the way to Kerala is an ancient place, rich in history, hemmed in by the Western Ghats on one side, open to the Arabian Sea on the other. It offers the most incredibly intricate network of diverse cultures and religions with their unique cuisines. This region was chosen and thoroughly explored to create a singular way of looking at local food. Visionary in her appreciation of regional cuisines when they were virtually unknown outside of the homes where they were created, Camellia Panjabi sent the original team of Chef Bernadette Pinto, Chef Sriram Aylur —who went on to set up Quilon, and pick up a Michelin Star in London —and Chef Naren Thimmaiah to garner recipes, and master ancient cooking techniques from homemakers in what was an entirely unorthodox way for a 5-Star hotel of 25 years ago, sometimes recruiting people who ran their own, small thattu kadas, tiny roadside Kerala tea shops that frequently served excellent but limited dishes, or even gifted home cooks. All of this experience, decades of it — with the accompanying techniques, traditions, complex flavours and styles of cooking —is distilled into a set of menus that are welcoming and easy to choose from.

![]()

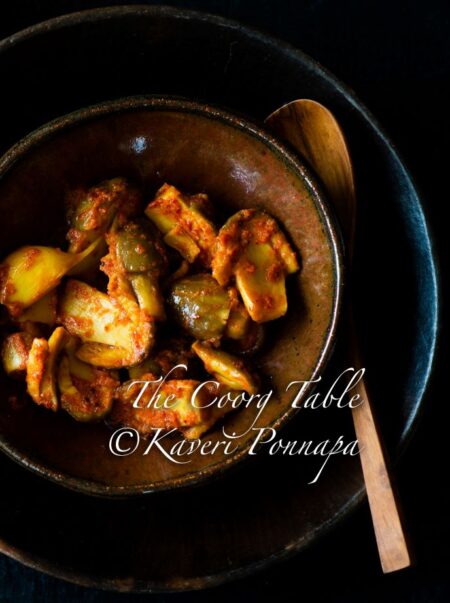

I have taken care to pick three dishes from a short selection of specials that changes with the availability of ingredients in season. Lingering over the plump, velvety cubes of mango preserved in brine, then cooked in a thick, rich, intensely flavoured sauce, it is quite apparent that one could only otherwise taste this Maavinakai Mensukkai in a Havyaka Brahmin home, which is exactly where it has been mastered by the Karavalli chefs. There is also Enne Badnekai, small, slit aubergines with a silky coating of ground peanuts and coconut, a hyper-local dish. The restaurant’s star dishes all come with their own, particular heritage: Crab Maligu Fry is a pepper-drenched stir-fry of tender mud crabs and Kori Gaasi has all the intensity of the Mangalorean original. Meen Pollichathu, a parcel of pan-fried pearl spot from Kerala’s backwaters, wrapped in a banana leaf, and Octopus Sukka, fried in the famous Kundapur spice blend have been cooked in homes for generations before making their appearance on your plate. The flavours are true to their pedigrees, sometimes with an interplay of 18 or more spices melded in perfect harmony. You are likely to come across endangered dishes like the ethereal Ramasseri Idly, steamed on a leaf-lined lattice of ropes tied across the rims of mud pots A slab of dark, smooth Dodol, or a delicately sweetened Ellanir Payasam draw out the essence of their specific ancestries. There are dishes from cuisines and communities as diverse as the Mapilahs of Malabar; Portuguese-influenced Goa; Konkani Brahmins of Mangalore and yet, the Karavalli chefs never miss a beat.

Behind the scenes, Chef Naren Thimmaiah runs a compact team of 8-10, some of whom may have been recruited on the basis of their mastery over a single dish There is a certain minimalist, focussed ethic of the home kitchen that is evident here. Thimmaiah — intense and driven beneath his smiling exterior — tastes, cooks with his team to ensure the flavours that fans have come to expect are intact and spends a good proportion of his day seeing that most of the raw materials, sourced from the regions where they are grown and produced reach their kitchens in perfect condition. Depending on what you have chosen to eat, the chillies in your dish come from Dharwar; coconuts from Kundapur; smoked Kudampuli from Kerala, toddy vinegar from Goa —and so the list goes on.

![]()

Karavalli has not been able to shake off its reputation of being a restaurant dedicated exclusively to seafood: during the annual Aqua Fest in November, there are over a dozen varieties of less known, sustainable seafood on offer. But the surprise is that nearly half the regular menu features the most refined and unusual vegetarian dishes such as Haaggalkai Kabbu Sari, bitter gourd cooked with sugarcane in a delectably creamy gravy. For regulars, there is the exciting prospect of a slight move inland that has expanded the menu to include Thaarav Roast, spiced duck, from the Syrian Christians of Travancore, and the immensely popular Koli Barthad, a rich, fried chicken flavoured with local vinegar from the Kodavas of Coorg.

Lists and awards often appear increasingly meaningless these days, crowding in names and trends that sometimes barely last a season or two. Karavalli’s attraction has just grown over the years. One gets the feeling that those stellar curries and neer dosas would taste the same without Karavalli having appeared twice on the S.Pellegrino 50 Best Restaurants in Asia list; recently, on Condé Nast Traveller’s Indian’s 50 Best Restaurants; NatGeo Traveller Magazine’s Top 10 best Restaurants in India and Jenny Linford’s ‘1001 Restaurants You Must Experience Before You Die’. It was the one stop Gaggan Anand, the best-known Indian chef in the world did not miss on a fleeting visit to Bengaluru. Quite unsurprisingly, Chef Naren Thimmaiah features amongst the Economic Times’ list of India’s Top Ten Chefs. There is a constant stream on international travellers, celebrities — both foreign and local —who never miss an opportunity to stop by. Thimmaiah and his team remain unperturbed by all the accolades and attention. As do the regulars —traditional South Indian extended families who arrive in large groups to enjoy the flavours of a favourite curry, as close to home cooked as possible: groups who have been dining here long enough to walk through the door with the comfortable air of being part of the establishment —a rare sight in most restaurants as famous as this one.

![]()

aravalli offers several culinary explorations in addition to their menu. At lunch, you can choose a balele oota, eating a set menu off a banana leaf. The Tiffin Carrier Meal is a take on a home-cooked office lunch, carried to work and shared with friends and colleagues. It arrives in a custom-made brass tiffin carrier, its stacked containers filled with a generous sampling menu of a selection of classics. Pothi choru is an unusual, one-dish meal of a banana leaf parcel traditionally carried on journeys, packed with small-grained, fragrant rice and chicken curry, the flavours of one permeating the other to make one, intensely delicious and perfect dish.

Karavalli: 66, Ground Floor, The Gateway Hotel, Residency Road, Ashok Nagar, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560025

080666 04545

By: Kaveri Ponnapa

This article was published in Sommelier India Magazine, Volume 15: Issue 1, January-March 2019 www.sommelierindia.com