There’s a particular warm, nutty fragrance that I associate with the time of year when the days are noticeably shorter and the nights longer and colder. It comes from a fine powder the colour of dark sand and it runs like silk through your fingers. It is made of just two ingredients –three, if you count salt – toasted, par-boiled rice and fenugreek –but for me, its nutty toastiness has the power of Marcel Proust’s madeleine, to evoke a sweep of memories from a world that has almost disappeared.  Thambuttu podi is prepared in homes across Coorg at the end of the year when the rice crop stands ready to be harvested in the fields, and mashed into ripe bananas to make a thick, sweet pudding that welcomes the harvest. (Read more at Harvests to Share) Just a whiff of its earthy warmth brings images of homes overflowing with multiple generations waiting to bring in the new grain, of lamplight and kitchen floors lumpy with piled up pumpkins, gourds and tubers. Its particular scent always reminds me of my grandmother. There’s a vivid picture of her in my head, pleading with an assortment of her grandchildren to try a bowlful of this special treat, all the while brandishing a large dinner fork to prove that she had not mashed the bananas by hand, as was the tradition. English boarding school education had bred its own kind of food snobbery, and some of my cousins refused to eat the stuff –how could they have missed the intense love in her voice, her eagerness to feed us this dish, the making and eating of it buried deep in some of the oldest traditions that made our homes and a community built around the cultivation of rice? After joining in the initial chorus of dissent, at the table, I always took an extra-large helping, mixed in hot, melted ghee, scraped coconut, toasted sesame seeds and sprinkling an additional shower of sugar over it all, ate fierce spoonfuls, driven as much by a love for its flavours, as for my grandmother.

Thambuttu podi is prepared in homes across Coorg at the end of the year when the rice crop stands ready to be harvested in the fields, and mashed into ripe bananas to make a thick, sweet pudding that welcomes the harvest. (Read more at Harvests to Share) Just a whiff of its earthy warmth brings images of homes overflowing with multiple generations waiting to bring in the new grain, of lamplight and kitchen floors lumpy with piled up pumpkins, gourds and tubers. Its particular scent always reminds me of my grandmother. There’s a vivid picture of her in my head, pleading with an assortment of her grandchildren to try a bowlful of this special treat, all the while brandishing a large dinner fork to prove that she had not mashed the bananas by hand, as was the tradition. English boarding school education had bred its own kind of food snobbery, and some of my cousins refused to eat the stuff –how could they have missed the intense love in her voice, her eagerness to feed us this dish, the making and eating of it buried deep in some of the oldest traditions that made our homes and a community built around the cultivation of rice? After joining in the initial chorus of dissent, at the table, I always took an extra-large helping, mixed in hot, melted ghee, scraped coconut, toasted sesame seeds and sprinkling an additional shower of sugar over it all, ate fierce spoonfuls, driven as much by a love for its flavours, as for my grandmother.

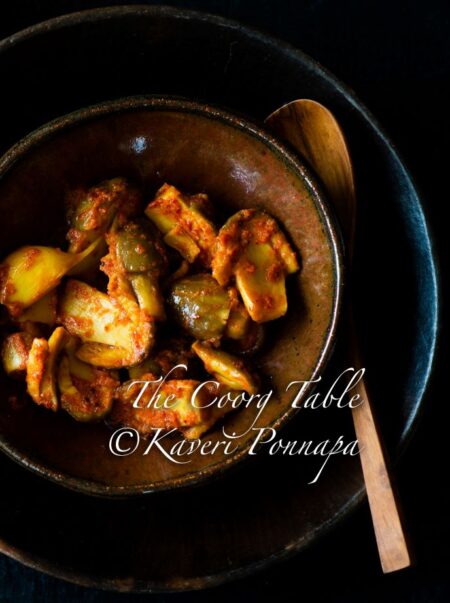

The small ceremonies and rituals of harvest night are all tangled up with the scent and texture of thambuttu podi. Mixed with mashed bananas, it becomes one of those frugal, comforting treats, which Coorgs love. It also makes a softer, sweeter pudding, berembuttu: a simple name taken from the way this very simple dish is made, from berevo, the action of spreading the cooked porridge onto a thatte, or thali and allowing it to set to a soft, spoon able consistency before it is showered with crispy sesame seeds and tiny, soft furls of fresh coconut.

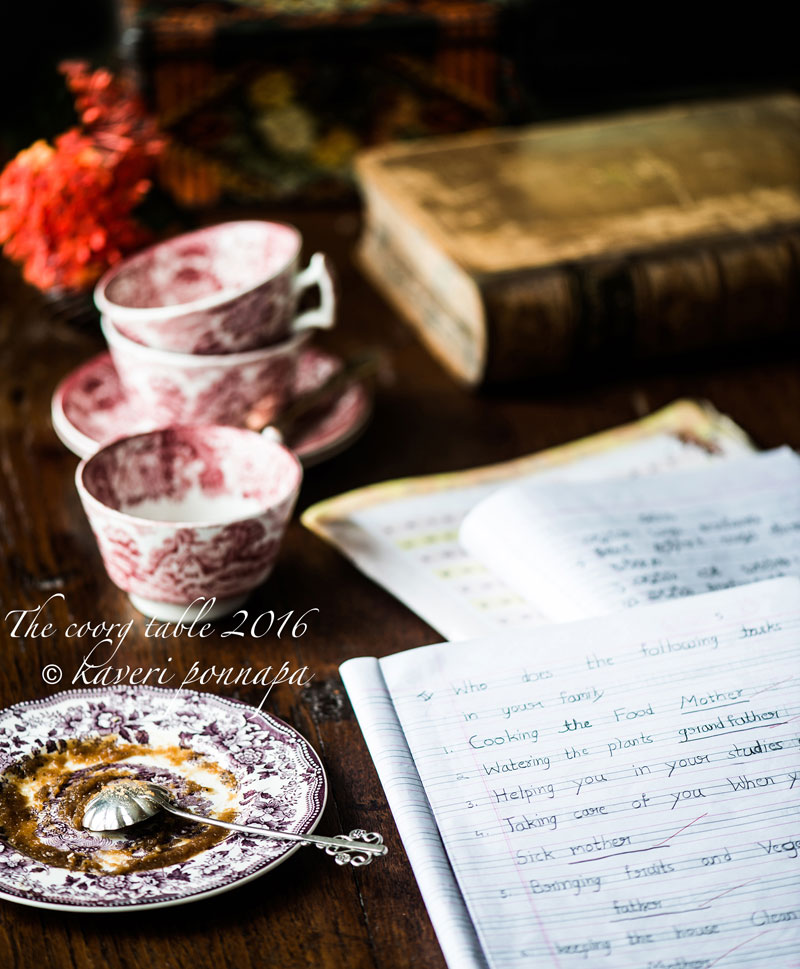

These days, there’s a beautiful, older woman who mentors me patiently, teaching me what she knows about the lost and forgotten foods of Coorg. Her voice is rich and deep, weaving in personal memories with descriptions of food quite seamlessly –can the memories ever be separate from the foods we have eaten, anyway? When she speaks about food and the kitchen, she is never frail and slow moving as she is now, but always strong, in her prime. She is patient and meticulous, pausing very often, checking to see if I have written down what she has just told me, accurately. It is as if she is sharing something very precious. And it is – these are the moments, days, weeks and years of her life spent creating food, learning subtle touches from her mother that make a familiar dish unique, all distilled into the stories and recipes she now hands me with profligate generosity. She is very precise in her instructions, making sure I understand exactly what she means –it is, after all, a legacy that she is passing on. We taste the dishes she describes or demonstrates and then we share meals she has cooked around her table. I never leave without small jars and containers, gifts from her kitchen, always something that she has made herself. Her words illuminate long gone moments so that I see them briefly, but vividly and unforgettably. Harvest was a hungry time, when people would stream into the house from working in the fields, demanding to be fed before they hurried back to more hard, outdoor work. For the women who presided over the kitchen berembuttu was quick and easy to cook –it was hot, nourishing, comforting and, with steamed offerings of the season –slices of pumpkin and puthari kalanji, a sturdy tuber –very filling. It was also the ultimate fast food, packed with nutrition. Unlike polished rice, all the rich nutrients were locked into the translucent, par-boiled grain making it a complex food, with a good surge of sugar from the dark, rich syrup of jaggery that was poured into it. It was made in enormous quantities and kept everyone going until they returned at the end of the day, work done, to a hearty dinner that was the main meal of the day. Women took charge of so many of the rituals at harvest, their presence needed everywhere in addition to managing the kitchen that I found myself wondering, in the days before gas fires and electric grinders, how much time was spent on the slow, careful toasting and hand-pounding of this rice, made in quantities to last the entire year, preserved carefully in airtight tins and jars. It was the ideal, ‘any occasion’ snack, especially popular with schoolchildren when they returned home, ravenous, with piles of homework to plough through. Even sixty years on, older friends cannot forget that the blank pages of a notebook that stretched endlessly seemed easier to fill with a bowl of hot berembuttu, which their mothers had just made, to help them along.

Her words illuminate long gone moments so that I see them briefly, but vividly and unforgettably. Harvest was a hungry time, when people would stream into the house from working in the fields, demanding to be fed before they hurried back to more hard, outdoor work. For the women who presided over the kitchen berembuttu was quick and easy to cook –it was hot, nourishing, comforting and, with steamed offerings of the season –slices of pumpkin and puthari kalanji, a sturdy tuber –very filling. It was also the ultimate fast food, packed with nutrition. Unlike polished rice, all the rich nutrients were locked into the translucent, par-boiled grain making it a complex food, with a good surge of sugar from the dark, rich syrup of jaggery that was poured into it. It was made in enormous quantities and kept everyone going until they returned at the end of the day, work done, to a hearty dinner that was the main meal of the day. Women took charge of so many of the rituals at harvest, their presence needed everywhere in addition to managing the kitchen that I found myself wondering, in the days before gas fires and electric grinders, how much time was spent on the slow, careful toasting and hand-pounding of this rice, made in quantities to last the entire year, preserved carefully in airtight tins and jars. It was the ideal, ‘any occasion’ snack, especially popular with schoolchildren when they returned home, ravenous, with piles of homework to plough through. Even sixty years on, older friends cannot forget that the blank pages of a notebook that stretched endlessly seemed easier to fill with a bowl of hot berembuttu, which their mothers had just made, to help them along.  Simple as it is to make a platter of berembuttu for a family of four, I can’t imagine what it must have taken to churn out a steady supply of it on a wood fire as people poured in, famished, while keeping one eye on the pumpkins and yams to be boiled and peeled at the same time. “How did you do it,” I ask my cookery teacher, “how did you manage to feed so many people, all of them so hungry? You must have spent hours in the kitchen and then gone back to work some more.” She thinks for a moment, and then smiles slowly. “I don’t know, now,” she says. “But those days, we just did it. And there were always the older women around us. We never knew women like that again. “What do you mean?” I ask. “Their voices,” she answers, the way they spoke to you, the way they called our names –there was so much love in them, and it all went into the food they fed us.” Somehow she does think to include herself in that long line of women she remembers, but I do.

Simple as it is to make a platter of berembuttu for a family of four, I can’t imagine what it must have taken to churn out a steady supply of it on a wood fire as people poured in, famished, while keeping one eye on the pumpkins and yams to be boiled and peeled at the same time. “How did you do it,” I ask my cookery teacher, “how did you manage to feed so many people, all of them so hungry? You must have spent hours in the kitchen and then gone back to work some more.” She thinks for a moment, and then smiles slowly. “I don’t know, now,” she says. “But those days, we just did it. And there were always the older women around us. We never knew women like that again. “What do you mean?” I ask. “Their voices,” she answers, the way they spoke to you, the way they called our names –there was so much love in them, and it all went into the food they fed us.” Somehow she does think to include herself in that long line of women she remembers, but I do.

Photo Credits: Nithin Sagi

All Food Styling: Kaveri Ponnapa

Please look out for the recipe in my upcoming cookbook

Thank you for visiting this page. If you read something that you enjoy, or see an image that you like, please take a moment to write a response. Do look out for the recipes of all the food featured here in my upcoming cookbook.

I just discovered you after following a link from Naomi Duguid ‘s site where she posted your interview with her. I’m thrilled to have your archives to read through. The articles you write are deep and informative and wonderfully written and illustrated. It’s like discovering a new country.

Hello Signe, thank you very much for all that you have to say about these pages, it is always wonderful to connect with someone who has enjoyed reading them. I’m so glad you found your way here, and I hope that you will keep reading the posts. I would be happy to answer any questions you may have about Coorg. Best wishes.Kaveri

I’ve read some of your writing before, and have always enjoyed it..

Your website is a treat! Beautiful pictures and your amazing writing. Even though I’m not from Coorg, I too have warm memories of my grandmothers, their smoky wood-fired kitchens and food whose taste has rarely been duplicated by anyone else!

Hello Ierene, welcome to The Coorg Table! Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts on these pages and the memories of your grandmother that they have brought to you. You don’t have to be from Coorg to enjoy these posts or recipes. Food is something that we all enjoy, with a mix of experiences in common and special memories, no matter where we come from, or live. I hope that you will keep reading, and do look out for the the cookbook, which I hope will have much more for you to enjoy. Warm wishes, Kaveri

Happy Puthari…Enjoyed reading… A wonderful writing with nice pictures….I do eat berembuttu, compared to berembuttu thambuttu I like more…Wow! your way of describing reciepes make us reading more interesting…Nice…Thanks for all your wonderful posts.

Happy Puthari, Kaverappa! I’m happy you enjoyed the post, do keep reading, and I there will always be something for you to like on this page. Warm wishes.Kaveri