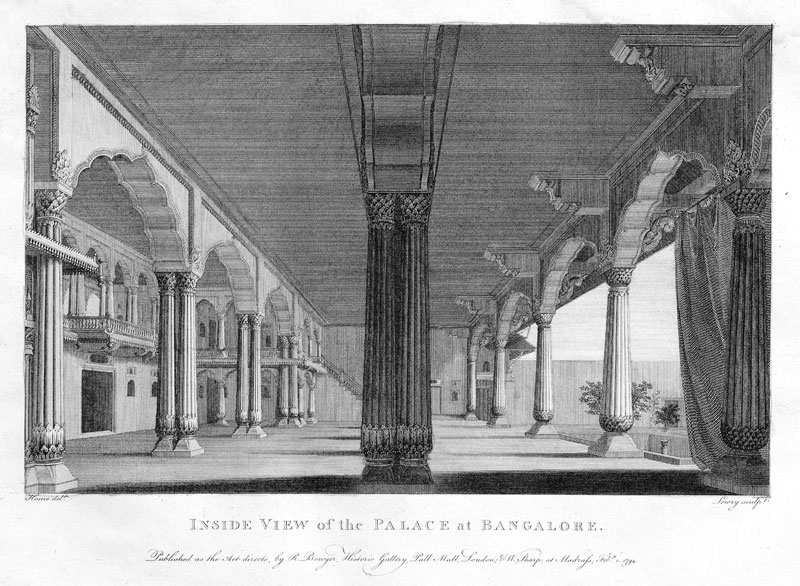

The town of “ …Bingrul… with its massive fort gates and strong fort walls (is) an impressive place. Deep ditches, full of water from the big tanks which are existing in its close proximity surround the fort walls. Within the town are fine buildings the most prominent among which is the palace. Atop the palace wave flags of different colours. On the walls of some of the houses are found paintings which are very good to look at. There are many commercial streets in this town with an array of shops displaying costly goods. At some of the squares of the town, fountains have been built from which water springs, giving a pleasing appearance. There are plenty of peacocks and pigeons here. The temples of this place are lofty and finely built.”  This seventeenth century description of the town of “boiled beans”, benda kala uru, supposedly named for an act of generosity on the part of a poor woman, who offered an exhausted and hungry king a plain meal of boiled beans, refers to the city which has found its place on the world map as the IT capital of India – Bangalore. It is a city expanding at a dizzying pace, ruthlessly consuming miles of countryside, re- creating landscapes and cultures as it moves, hurling a strident modernity of lifestyle and architecture at the waves of young migrants who flock to it, seeking jobs in the industry that made it a global by word for innovation. Wide swathes of green paddy fields, airy coconut plantations and cool, shadowy, mango groves were swept away in less than a decade, and the rural fringes of a small city gave way to a world of pubs, uber smart bars and restaurants, luxury hotels and fashion, a “global lifestyle”, lived mostly out of high – rises drive this metropolis.

This seventeenth century description of the town of “boiled beans”, benda kala uru, supposedly named for an act of generosity on the part of a poor woman, who offered an exhausted and hungry king a plain meal of boiled beans, refers to the city which has found its place on the world map as the IT capital of India – Bangalore. It is a city expanding at a dizzying pace, ruthlessly consuming miles of countryside, re- creating landscapes and cultures as it moves, hurling a strident modernity of lifestyle and architecture at the waves of young migrants who flock to it, seeking jobs in the industry that made it a global by word for innovation. Wide swathes of green paddy fields, airy coconut plantations and cool, shadowy, mango groves were swept away in less than a decade, and the rural fringes of a small city gave way to a world of pubs, uber smart bars and restaurants, luxury hotels and fashion, a “global lifestyle”, lived mostly out of high – rises drive this metropolis.  But Bangalore, perched in a landscape of gargantuan, tumbled boulders, and awe-inspiring rock outcrops of unfathomable antiquity, has a timeline that links it to Neolithic settlements that existed a millennium before the birth of Christ. Caches of Roman coins, one of them unearthed while extending the runway of the old airport, throw up an older existence, possibly on an overland trade route between the East and West Coasts. The histories of several dynasties have unraveled across the backdrop of the Deccan Plateau, on which Bangalore is situated – the Gangas, the Cholas, the Hoysalas have all claimed this region as part of their empires over the slow centuries. They left their imprint in large numbers of inscriptions and, in one of them, the name Bengaluru appears, traced to a small, 9th century CE settlement ruled by Ganga kings.

But Bangalore, perched in a landscape of gargantuan, tumbled boulders, and awe-inspiring rock outcrops of unfathomable antiquity, has a timeline that links it to Neolithic settlements that existed a millennium before the birth of Christ. Caches of Roman coins, one of them unearthed while extending the runway of the old airport, throw up an older existence, possibly on an overland trade route between the East and West Coasts. The histories of several dynasties have unraveled across the backdrop of the Deccan Plateau, on which Bangalore is situated – the Gangas, the Cholas, the Hoysalas have all claimed this region as part of their empires over the slow centuries. They left their imprint in large numbers of inscriptions and, in one of them, the name Bengaluru appears, traced to a small, 9th century CE settlement ruled by Ganga kings.  The making of a city, as David Hall wrote of 5th century Athens, lies not in a sudden event, but in the culmination of a long process. But if we had to look for a single moment in time, when the idea of Bangalore as we recognize it was born, we would turn, inevitably, to the year 1537CE, to the dramatic image of a local chieftain, the Yelahanka Nadu Prabhu, Kempe Gowda I, under the authority of Vijayanagar, choosing an auspicious moment and ordering four milk white bullocks to be harnessed and driven by four young men, to furrow the earth in four cardinal directions, laying the main streets to his new capital. Kempe Gowda chose the location for his fort, so the story goes, because he saw a hare chasing a hound. He named the place Gandu Bhoomi, or Heroic Land, perhaps quite unwittingly prophesying the important military role Bangalore would play for almost 400 years to come. A blurred imprint of Kempe Gowda’s original furrows still exists in the heart of the city, in the oldest streets in Bangalore- Chickpet and Dodpet – congested, narrow, but teeming with life, carrying on the rhythms of centuries.

The making of a city, as David Hall wrote of 5th century Athens, lies not in a sudden event, but in the culmination of a long process. But if we had to look for a single moment in time, when the idea of Bangalore as we recognize it was born, we would turn, inevitably, to the year 1537CE, to the dramatic image of a local chieftain, the Yelahanka Nadu Prabhu, Kempe Gowda I, under the authority of Vijayanagar, choosing an auspicious moment and ordering four milk white bullocks to be harnessed and driven by four young men, to furrow the earth in four cardinal directions, laying the main streets to his new capital. Kempe Gowda chose the location for his fort, so the story goes, because he saw a hare chasing a hound. He named the place Gandu Bhoomi, or Heroic Land, perhaps quite unwittingly prophesying the important military role Bangalore would play for almost 400 years to come. A blurred imprint of Kempe Gowda’s original furrows still exists in the heart of the city, in the oldest streets in Bangalore- Chickpet and Dodpet – congested, narrow, but teeming with life, carrying on the rhythms of centuries.

By the time he bequeathed his kingdom to his successor, Kempe Gowda’s mud fort, with its eight gates, its petes, or markets, and two magnificent temples -the Gavi Gangadaresvara, and the Basava Temple – were enclosed by a deep ditch and a thick, defensive hedge of thorny trees . Four iconic watch -towers, located at the cardinal points, famously marking the potential future limits of the city, were built by his son, Kempe Gowda II – a vision of Bangalore had begun to emerge, elements of which would last right into the 21st century. When Lewin Bowring wrote in the 1850’s, two of these towers were still well beyond the boundaries of the city – these towers have long since been engulfed by a city whose hunger for expansion seems to know no limits, and the southern tower, set on an arc of ancient rock, was declared a national monument in 1975.

Major Dirom, writing during the campaign against Tipu Sultan, in the 18th century, observed that the countryside between Bangalore and Hosur was “…fertile (and) varied…, beautified by chains of tanks for the culture of the low grounds, and with numerous villages and small forts; which, surrounded with trees, crowned and adorned every eminence.” The lush countryside, with its acres of ripening crop, the backdrop of the hills, and above all, the cool climate made him remark that the scene “…resembled more a peaceful country in Europe, in the midst of spring, than the seat of war in the height of summer between the tropics in India!”

One of the most picturesque and, unique expressions of an emerging Bangalore, that captured the attention of the earliest visitors, was its tanks, known locally as “keres“. Since at least the 8th century CE, a series of linked, man-made irrigation tanks have transported water to river-less Bangalore, on its high plateau. Water has been a perennial problem, still unresolved, and through the ages, it was these man made reservoirs that fed the city and the neighbouring countryside. Practically every government added to these water bodies, including the British colonial administration, which built the interlinked Millers Tanks, in1873. The years 1875-1877, records the historian Fazlul Hasan, were years of acute drought, when the tanks dried up. The “bhishti“, or water carrier became a familiar figure, selling water from a leather bag, carried over the shoulder. Bangalore today, appears to be in the grip of a perpetual drought, brought on by a population growing at an unprecedented rate, and scores of modern day “bhistis” roam the streets and suburbs of the city, selling water from tankers. Neither the Sankey tank built in 1882, nor the Chamarajendra Reservoir of 1896, nor the Thippagondanahalli Reservoir of 1933 could cope with the needs of a city that could not stop growing – old battles continue to rage between governments, over the allocation of river waters.

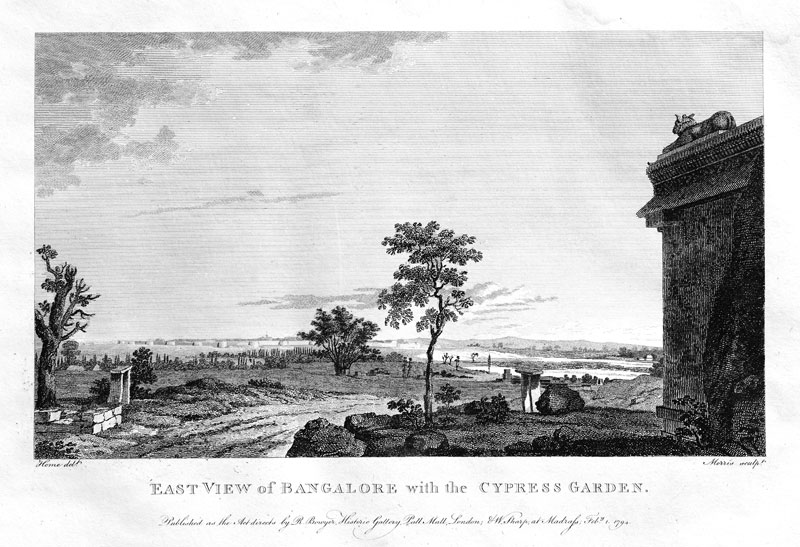

Many of Bangalore’s modern identities have deep roots in its past – the Yelahanka Nadu Prabhus, Kempe Gowda’s ancestors, were farmers, and took great care to develop the neighbouring countryside for agriculture. The tradition of farming and gardening, in and around Bangalore, observes Fazlul Hasan, is over four centuries old, and the Garden City, as old as this tradition. One of the city’s best- loved landmarks, the Lal Bagh Gardens,was the creation of Hyder Ali, possibly inspired by the French gardens he saw in Pondicherry. For a father and son – Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan – who inspired fear, and awe for their military acumen and ferocity on the battlefield, the commitment and passion with which the Lal Bagh was developed is astonishing. Heriditary gardeners were invited from Tamil Nadu to settle in the environs of Bangalore, and tend the Lal Bagh.

Lewin Bowring, the first Commissioner of the city wrote that “… the visitor might at first imagine himself transferred to a purely European pleasure garden, till advancing, he sees the gorgeous creepers, the wide spreading mango and the graceful betel-nut trees which characterize the East. The garden is a beautiful retreat and is frequented by all the classes….” This lush retreat, a place of the imagination, lies at the foot of a sprawling arc of primeval rock, atop which is perched one of Kempe Gowda II’s watchtowers. Hyder’s son, Tipu Sultan spared no expense importing seeds and plants from Mauratius, Turkey, Afghanistan and Persia for this unique garden, and even imported the knowledge of sericulture -the Mysore silk weaving industry owes much to this man of many interests, who introduced sericulture to the areas around Bangalore.

Each time Bangalore changed hands, new rulers added to the landscape, creating new parks and gardens. Many localities still carry the names – Coles Park, Langford Gardens, and Richmond Park. In 1864, Cubbon Park, the continuing pride of Bangalore, was created in the new administrative heart of the city.

The Lal Bagh was revived by the colonial administration, and The Glass House, a scaled down replica of the Crystal Palace of the Great Exhibition of London was re-created in the heart of the garden, in 1889. The British themselves introduced many exotic plants, vegetables and trees that are now so familiar, that they define the character of the city itself. The plantings of flowering trees, undertaken by generations of administrators and planners paint avenues and streets in different colours, according to the seasons. The climate and soil of the city were particularly suitable for horticultural experiments by a colonial administration interested in the propagation of new fruits and vegetables, in the interests of a growing numbers of British nationals who were making a life in India.

There are several moments in Bangalore’s history that prefigure the tremendous mix of people and their distinctive cultures that make up the population of the city today. The IT industry draws talent from across the country; restaurants serving diverse ethnic foods have sprung up everywhere and, at malls and street corners, you are as likely to hear Bengali, Punjabi and Hindi spoken, as Kannada and many pockets of sub-cultures have begun to evolve across the city. Early 17th century Bangalore, as the jagir of the Maratha leader, Shahji Bhonsle absorbed diverse cultural streams as artists, musicians and government officials from Pune made the city their home, resulting in a plurality of thought, great creativity and tolerance. A little later, the Mughals would occupy and garrison the city for three years creating new patterns of language and culture. 1956 would bring another wave of enriching exchanges in literature, language, music and food, when the Kannada speaking areas of the old Madras, Hyderabad and Bombay states were amalgamated with the old Mysore state.

Another, smudged identity sometimes floats to the surface, of Kempe Gowda’s Ganda Bhoomi, a Heroic Land. At different times, and sometimes simultaneously, the restless armies of the Gangas, Cholas, Hoysalas, the Marathas,the Qutab Shahi Sultanate and the Mughals were a strident presence across the rocky tableland of Bangalore, at the heart of campaign country. The soaring rock outcrops west of the city, the famous Doorgs or hill forts, were held by local chieftains, and there was an incessant movement of hard –riding, battle-hardened men across this ancient terrain. These natural rock fortresses of pharonic proportions lent a singular character to the countryside, intimidating and awe-inspiring. Bowring, writing of Savandurg, described “… a stupendous rock of granite, 4000 feet above sea-level, and resembling in appearance a gigantic whale…. The mountain (was) smooth and precipitous on all sides with a circumference of many miles, and was surrounded by a thick jungle of bamboos and other trees which made the rock unapproachable.“

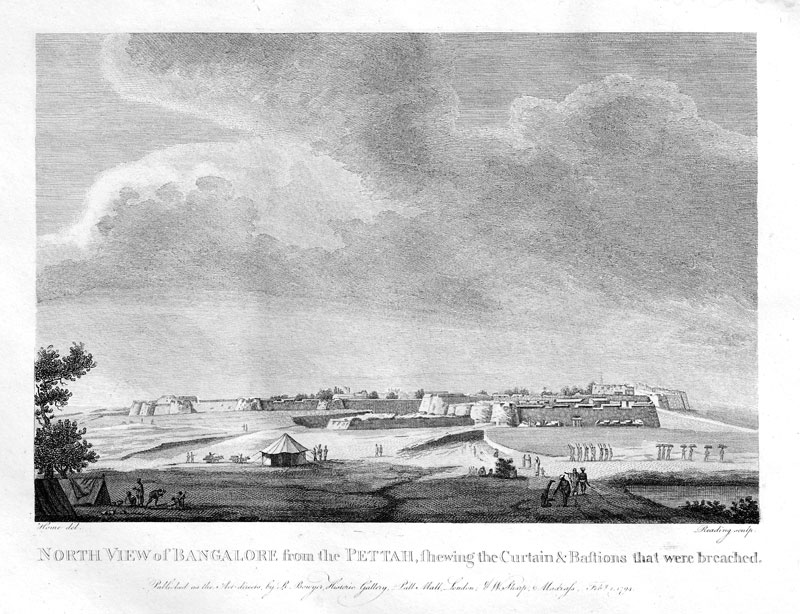

Kempe Gowda’s original mud fort, with its deep ditch and thorny hedge- which was finally removed and the ditch filled up, in 1861- that thwarted the agile Maratha cavalry had it’s defences strengthened by Chikka Deva Raja of Mysore, when the city passed into his hands. He built a second fort to secure the city against attack. Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan added their own fortifications and, finally, the British built a sprawling cantonment town to accommodate their troops after the final war with Mysore. Beyond Bangalore lay the fertile hinterland of Mysore country. In its existence, Bangalore has been a strategically important stronghold in the politics of the Deccan. Buffeted by the forces of history – sold; awarded as a fife; besieged; attacked; conquered, looted and bartered, it nevertheless, retained its unique character.

When the Maratha leader, Shivaji, who had spent the first twelve years of his life in the city, heard that his half –brother, Venkaji, was planning to sell the Maratha jagir to the ruler of Mysore, he reacted with a strong challenge. In a dramatic sequence of sabre- rattling, outright war, treachery, military brilliance and courage, he won Bangalore from Venkaji in 1678CE. But within two years, the city would slip out of Maratha control into the hands of the Mughals, only to be sold by a retreating Mughal Governor to Chikka Deva Raja of Mysore. The Marathas would try and retrieve their old jagir, but ironically, their defeat at the hands of the Mysore forces would result in Bangalore and its environs being handed over to one of the most famous men in history – Hyder Ali Khan. And under Hyder, writes Fazlul Hasan, the city would become “…a great recruiting and military centre in the south…” playing a historic role in the four Mysore Wars between Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan and the British.

Bangalore under Hyder Ali and Tipu was very much a military city,full of French mercenaries from Pondicherry, with a foundry to build cannons, gunsmiths, sword makers, godowns and magazines for ammunition. Fazlul Hasan observes that, in 1780, it presented “…a picture of a vast military camp….“

The armies of the day were more like small nations on the move, and Major Dirom, writing of their native allies in the Anglo- Mysore wars noted that “…it was highly entertaining to see them in motion the whole day; the chiefs in different group… themselves and their principal attendants mounted on elephants, distinguished by their state flags and nagars, also borne on elephants. They were surrounded by cavalry, with their various standards, and preceeded by their bards, and bands of music, who sung the praises of their master and the heroes of their nation…. A spectacle so wild and irregular, yet so grand and interesting, resembled more the visions of romance than any assemblage than can be supposed to have existence in real life.” The Maratha camp, with its colourful tents, jewellers, smiths and people of every trade and description appeared to Dirom, “…as if they were in Poonah, and at peace” rather than at war.

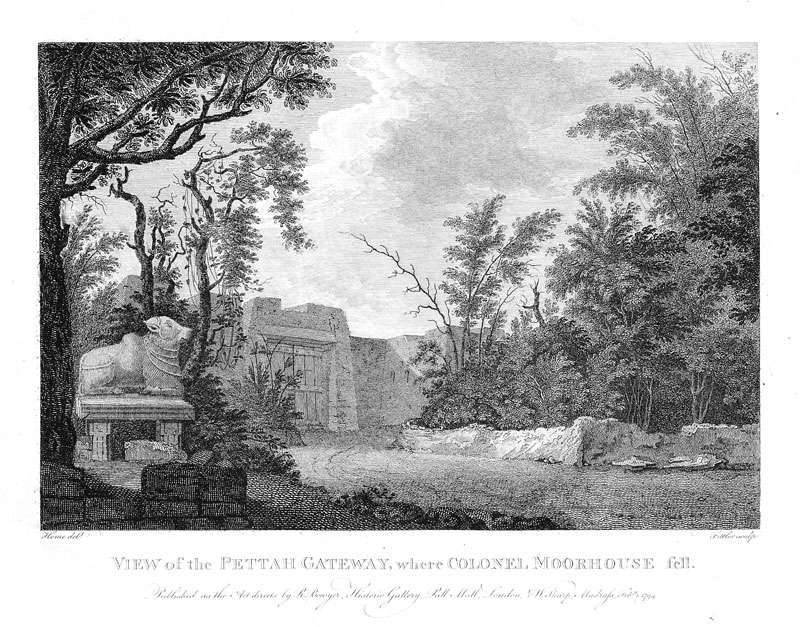

Another account describes, with astonishment, that the soldiers of both armies “…mingled at the tank, put on their armour, ate their rice and chewed their betal, gossiped and chatted together.“It was these unwieldy, lumbering armies that Hyder and Tipu restructured, modernized and disciplined,with French help, to take on the expanding British power in India, with Bangalore as his first line of defence. And it was Bangalore that bore the brunt of the British attacks during the Mysore Wars, until the fall of Srirangapatanam, in 1799. Some of the most famous battles of the British in India were fought in the vicinity of Bangalore, and the storming of the Halsoor Gate, would inspire many paintings, sketches and prints. The prosperous city was thoroughly looted, and occupied by British troops for a year.

In 1809, after the defeat and death of their enemy Tipu, the British, who had stationed troops at his old capital, Srirangapatanam, had them withdraw to the cooler and healthier climate of Bangalore, and Lt. Blakiston was given the responsibility of laying out a brad new Cantonment. The British, who brought with them surveyors, cartographers and all the paraphernalia of Empire building, chose the village of Halsoor for what was to become a large, well planned Cantonment. Barracks, churches and spacious bungalows were spread over a neatly planned grid, hemmed in by the South Parade, now M.G. Road. Infantry Road, Artillery Road and Brigade Road are all current names that survive from that era, recalling an area once as clearly separated from the old town, or pettah, by demarcations of space as by the divisions of race and rank.

The Cantonment engulfed neighbouring villages rapidly and, the Lt. Winston Churchill wrote that, “All the distances in the spread -out cantonment were so great that walking was impossible. We cantered on hacks from one place to another.”

What he saw around him was, “Splendid roads, endless double avenues of shady trees, abundant supply of pure water; imposing offices, hospitals and institutions; ample parade grounds and riding schools….” There was every impression of permanence and a grand scale in the planning of the Cantonment – the British had come to stay. The architecture of this preserve was distinctive and, Lt. Churchill, along with two friends, “…took a palatial bungalow, all pink and white, with heavy tiled roof and deep verandahs, sustained by white plaster columns, wreathed in purple bougainvillea.”

The social life of the new rulers was quite distinct from that of the natives, and institutions like the Bangalore Club – where Winston Chruchill left an unpaid bill -and the Bowring Institute, were created as spaces quite suspended from their surroundings, enclosing a transplanted culture. The barriers between alien cultures did not remain quite so distinct for long, however, and before long, Bangalore had a strong and thriving Anglo-Indian community, a unique part of its identity, who contributed richly to the character of the new city.

Several fine churches from the colonial period, like Trinity Church, St.Patrick’s and St. Andrew’s are still a part of Bangalore’s heritage, but the mellow, secular architecture of the period was swiftly swept aside by the hard glitter of glass and steel that the intense pressure on housing for the great influx of IT personnel from the late ’90’s brought in its wake. The old Cantonment survives in environs of the Madras Engineer Group Centre, one of the oldest regiments of the Indian Army, once made up of the sappers and miners who helped the British map, tame and build the up the countryside they conquered. This oasis of green, with its remnants of colonial architecture is separated by the expanse of the Halsoor tank, from one of the four watchtowers of Kempe Gowda in the distance. The city continues to be the recruitment centre for the southern region, for India’s modern Army, and is the location for a number of important Defence establishments, like H.A.L, I.S.R.O and N.A.L.

So where did Tech City have its beginnings? Hyder and Tipu were dynamic and forward thinking in their ready acceptance of the manufacture of modern weapons and heavy guns, and current European methods of warfare. Were there hints of the Bangalore to come when, in 1806, William Lambton began his baseline for the phenomenal survey of India, known as the Great Arc of the Meridian, from Bangalore? Or was it there in the slew of Public Sector enterprises – H.A.L, H.M.T, Bharat Electronics, which coloured the identity of Bangalore for decades?

In the mid-1980’s, a satellite dish would arrive, borne on a bullock cart, delivered to Texas Instruments, enabling them to set up a software design centre in the city, the first foreign company to do so. The rest, as they say, is history. Today, Accenture, I.B.M, Oracle, Dell, Cap Gemini,HP, Cisco and every international technology giant is a part of Bangalore’s landscape; Inofsys and Wipro are landmarks and pilgrimage centres in this IT driven city, which generates business worth billions of dollars. Sourcing is slowly giving way to innovation, especially by the smaller players in this gigantic market.

Today, Accenture, I.B.M, Oracle, Dell, Cap Gemini,HP, Cisco and every international technology giant is a part of Bangalore’s landscape; Inofsys and Wipro are landmarks and pilgrimage centres in this IT driven city, which generates business worth billions of dollars. Sourcing is slowly giving way to innovation, especially by the smaller players in this gigantic market.

The new Tech City was the inspiration for Thomas Friedman’s ‘flat world’, which also, as he observed, put people and cultures into close contact with each other, perhaps faster than some of them could cope with. In a city filled with expatriates, droves of returning Non-Resident Indians and a workforce of technically skilled young people from right across the country, many cultures and nuanced identities co-exist. Gated communities enclose luxury villas and self-contained communities, excluding the debris and chaos of a city growing too fast for itself. New suburbs rise so quickly that many residents do not even know of their existence. The ancient rocks of the Deccan Plateau, from which the Neolithic tools found around Bangalore were carved, provide an endless supply of material for all these new settlements. Basavangudi, a fragment of Kempe Gowda’s original pete still measures out its life to the rhythm of temple bells; the crush and din of Chickpet, lined with tiny shops spilling out treasures onto its narrow streets continues to attract a clientele faithful to its hidden charms, over the lure of soaring, glitzy malls, full of luxury brands. Devanahalli, where Hyder Ali first distinguished himself in battle, and rose to fame, to be given command of 50 horse and 200 foot soldiers is now synonymous with Bangalore’s international airport. Pockets of tradition linger in Malleshwaram and Jayanagar, where you can catch concerts of both Hindustani and Carnatic music of rare quality, in settings, where comfort is non existent, but every member of the audience a connoisseur, while the outward sprawl of multi-storied suburbs spawns many new, hybrid cultures, and every day brings a tussle with the question of identity.

Whichever way you look at it, the city of Bangalore has spilled beyond the limits of Kempe Gowda II’s watchtowers, literally and metaphorically, borne on a vision far more expansive than either its founder, or any of its inheritors could have imagined.

This article was published in the Taj Magazine, Vol 40.No 1.

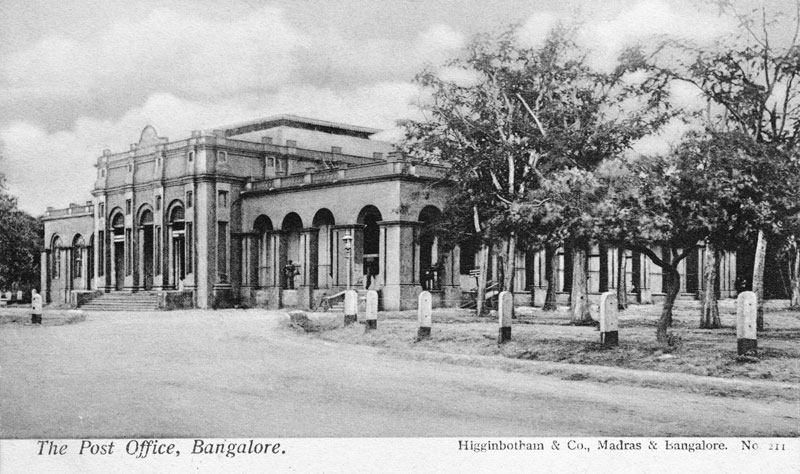

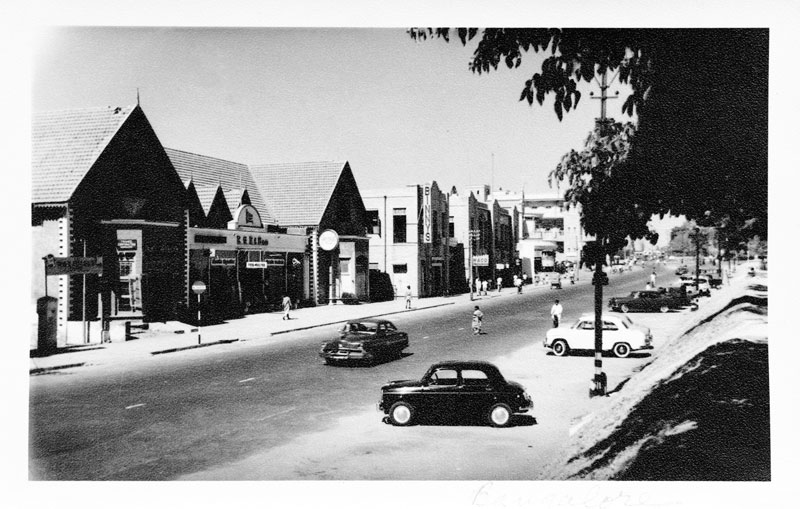

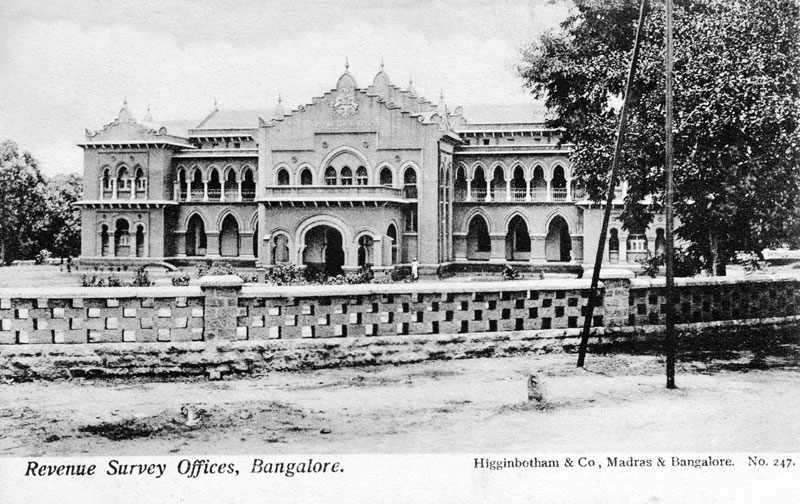

Image Courtesy: The Taj Magazine

Beautiful pictures. I would like to know the names of the temples shown here. Thanks for sharing.