Captivated like so many others, by the beauty, artistry and perfection of Japanese cuisine, its uncompromising freshness of ingredients and oneness with the rhythm of the seasons, I often read Shizuo Tsuji’s passionate outpouring of love for his native cuisine, to look at the food on my plate through Japanese eyes. And of late, I have become addicted to the adventures of an unlikely gastronome – Yamaoka Shiro, the sloppy young journalist from the Tozai Times, who works his highly unorthodox way through all the refinements of Japanese ryori. Oishinbo, or The Gourmet – the name woven together from the words oishii, or delicious, and kushinbo, one who loves to eat – the manga, or graphic novel with over100 million copies sold, is where you can learn, painlessly, to tell your sunomono and aemono from your agemono.

Yamaoka Shiro has been commissioned by his newspaper to create the Ultimate Menu, capturing the genius of Japanese cuisine. The antipathy between the casual, rebellious Yamaoka Shiro, and his polished aesthete father, Kaibara Yuzan, the founder and director of the Gourmet Club, who decides to pit his vast knowledge of food against his son’s by heading the Supreme Menu, commissioned by the Teito Times, a rival newspaper, drives each of the episodes, in a fascinating exploration of the nuances of Japanese food, as father and son try to topple each other in culinary battles.

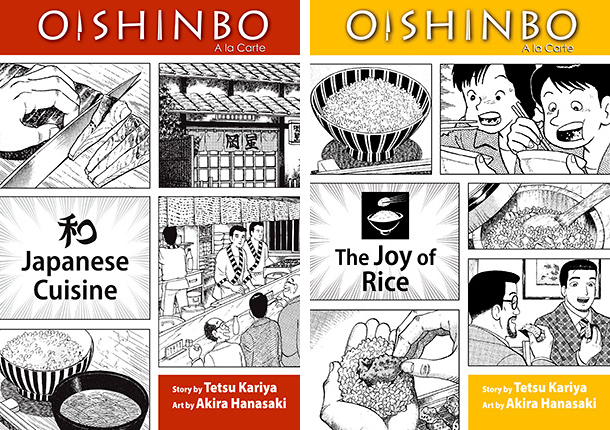

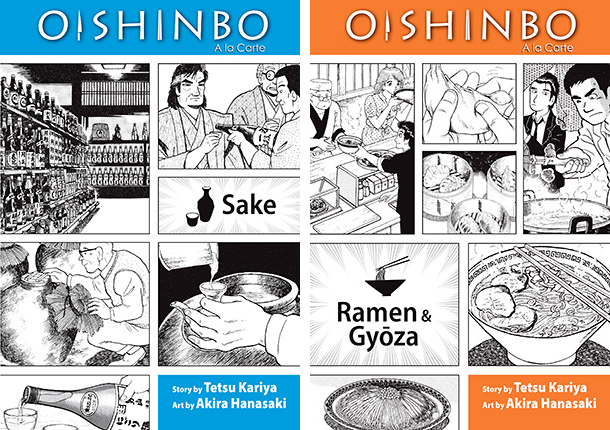

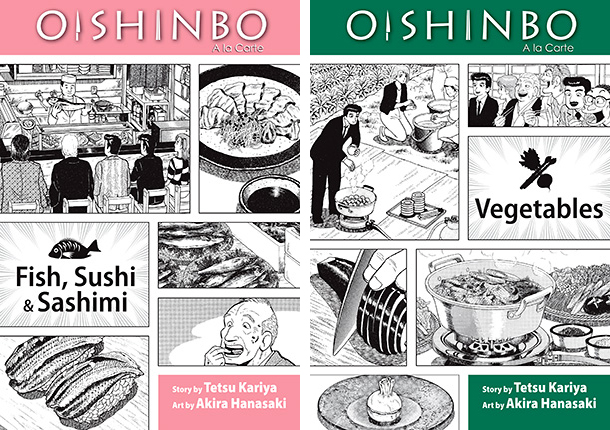

Each volume of Oishinbo A la Carte is dedicated to a single aspect of Japanese cuisine: Ramen and Gyoza; Fish, Sushi and Sashimi: Japanese Cuisine; Sake; Izayaka: Pub Food; Vegetables, and my personal favourite, Joy of Rice. The stories read from left to right, like the original Japanese, so that the artwork remains undisturbed, which is sometimes confusing. But the notes at the end explain all the terms used, from the more familiar katsuobushi (dried bonito, or skipjack tuna) to karasumi (salt-cured, sun dried mullet roe).

With a large population, and extremely limited arable land, the underlying philosophy of Japanese cuisine was born of cooking with limited raw materials and, therefore, a need to “let little seem like much, as long as it is fresh and beautiful.” The individual flavours of foods are highly prized, with seasonings kept light and, presented on the table in antique ceramics with hand shaved cedar wood chopsticks, or at the very least, aesthetically chosen vessels which complement the creation, the food very often has a painterly quality, with symbolism in the use of a garnish, to evoke, for instance, a season. And so the aesthetic of raw fish in sushi and sashimi, and dashi, made from simmered kelp and shavings of bonito, a broth by which, according to tradition, the standards of the chef can be judged. This simple, fragrant stock, and soy sauce, along with fish and rice, is the cornerstone of a sophisticated cuisine.

Often tactless, and unorthodox – he seeks out garbage sorters who eat leftovers, to find out the best new chefs in the area, and swims Akashi Strait to understand the sea bream found in it’s waters – Shiro, trained by his father, has a deep knowledge of food, with flashes of inspiration. But he sometimes loses to Kaibara’s superior experience. Kaibara, an obsessive, critical, perfectionist is such a tyrant, that he is referred to as a “gourmet demon” by one of the characters. Shiro has left home after destroying his father’s valuable ceramics and paintings, protesting against this culinary tyranny. The clashes between father and son, as they meet unwillingly, or challenge each other at various inns and ryotei, the extremely refined restaurants where one may dine only if one possesses the right credentials, are lessons in brinkmanship, and gourmet cooking.

Amusing, informative, Oishinbo expounds on the principles of cooking, techniques, the etiquette of eating, the art of presentation, the tea ceremony; Japanese ceramics, nutrition and environmental issues with ease. It’s a treat to read of the rare specialties of different regions of Japan, like tokobushi abalone, rare even for the Japanese, which we are unlikely to taste, presented in lively detail, along with the superior artwork of the food and dishes.

Rice, so sacred that it’s synonymous with food, is often treated like art, in Japan. Some time ago, a friend sent me pictures of the most incredible crop art, where farmers plot the planting of varieties of rice, whose leaves grow in different colours. In Inakadate Prefecture, the figure of a Sengoku warrior on horseback appears in the fields, as the crop grows. These works of art have to be viewed from an elevation, and different Prefectures have their own designs.

The rice ball, considered to be the epitome of Japanese food, is the theme of a contest and the run through exquisite combinations of flavours is so engrossing, that we don’t mind quite so much when Shiro loses to his father’s superior experience. In the gyoza round (half moon dumplings, with different fillings) however, it’s the pompous Kaibara’s turn to bow to his son’s ingenuity, when he invents a filling of melted muscovado sugar.

Although the story line is thin – cooking challenges abound, whether to gain someone’s hand in marriage or to attract tourists, Oishinbo presents many debates which are current, such as the importance of maintaining traditions, while accepting influences from other cultures – the Japanese, for all their insularity, have absorbed culinary influences from China, Portugal and India, amongst other countries.

The importance of discussion, and the emotional appeal of food, often ignored by Kaibara, is endorsed by Shiro – we see a Kyoto millionaire almost weeping with joy over a dried sardine from his hometown. And while this is an engaging way of working one’s way through the food traditions of Japan, some of the issues raised are serious, which we ourselves are facing today – disappearing local delicacies; lost culinary techniques; the sterility of tradition that does not adapt; dwindling agriculture; the import of inferior, ready prepared foods; tiny establishments that sell excellent food being replaced by pizza chains and burger joints; and generations growing up without any experience of the best food traditions of their country.

This article appeared in Food Lovers Magazine Vol.5 Issue 4, August/September 2011

Image Credits: K.P.Ponnapa