“On Sunday evenings a great deal of noise and tumult prevailed in the back region as a result of arrack drinking, and the shrieks and yells that were borne in upon the breeze might indicate that…a fight was in progress….”

Every plantation cook I ever encountered loved the bottle. In my grandmother’s remote coffee plantation home, the daily ravages of country liquor meant raised voices and the terrible din of pots and pans striking each other, a cacophony that made its way into the dining room. My grandmother finally won the battle (almost) every single time, emerging triumphant from the smoky, chaotic kitchen, the pleats of her sari held firmly behind her.

By dinner time, peace usually prevailed in the form of perfectly cooked courses presented at the table. Her cook was a stick-thin figure, generally cheerful, always dressed in a colourful, chequered lungi, which he transformed into formal attire of sorts by donning a clean white shirt over the flapping garment while he served us dinner.

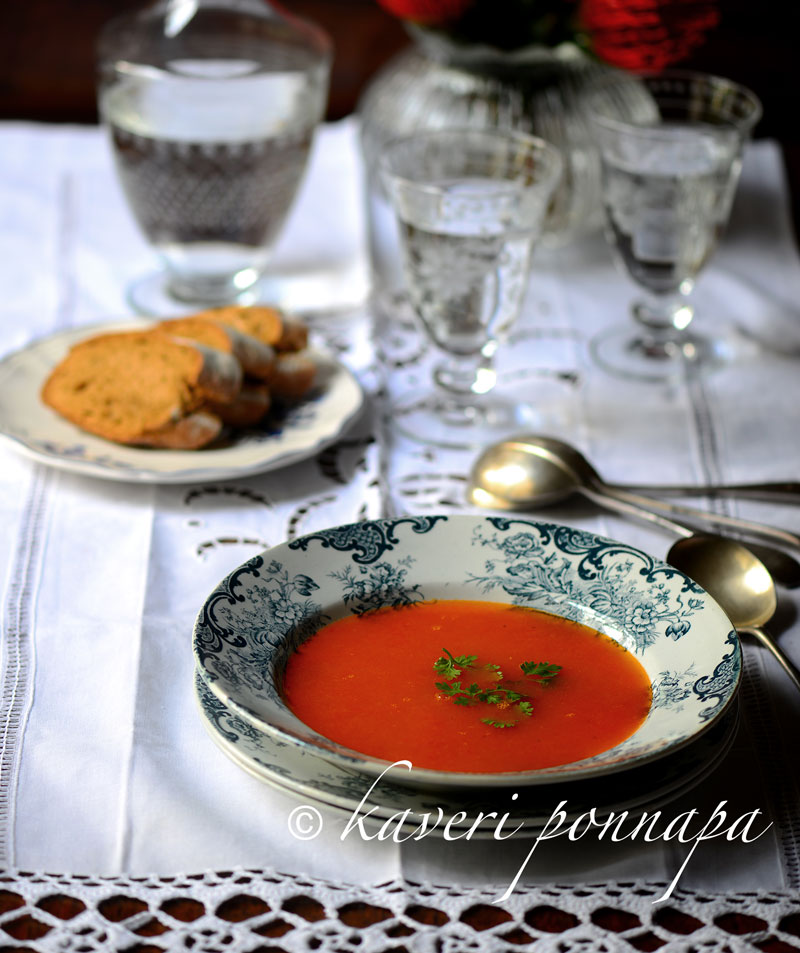

Tomato soup, when he cooked it, had an elusive, warm, smoky flavour with a hint of spice. It was just thick enough, without the usual additions of milk or fresh cream, and relied almost entirely on the concentrated flavours of well-ripened tomatoes. It had a certain rustic taste to it that was hard to describe. Perhaps you could call it a country soup. Small, golden globes of oil floated on the surface, and a heap of fried croutons were served separately. The soup was a vivid orange – perhaps he added a drop of cochineal, as cooks often did, to any and every dish that they could. I will never know. But the sweetness of the tomatoes came right through, softened and rounded by that wonderful smokiness.I can’t recall how the original soup was made, but I imagine it picked up that smoky patina from the thick, pungent wood smoke that frequently enveloped the kitchen. I finally re-created the tastes by charring tomatoes over a live flame and then cooking them into a soup that was satisfyingly close to the taste that obsessed me all these years: a taste which could never be ruined, even under the influence of copious quantities of country liquor.

Tomato Soup Recipe

- Take four to six, large, ripe tomatoes, wash and pat them dry. Pick them up with grilling tongs, and char them over hot coals, or an open flame. Cool, and peel away the skin. Meanwhile, wash and soak about two tablespoons of split masoor dal in water to cover. Chop the peeled tomatoes roughly and set aside. Slice one or two large onions. Place a pressure cooker over medium heat, and drop in a knob of butter. When it melts, add the sliced onions and fry until translucent. Now toss in the chopped tomatoes with their juices with whole black peppercorns and salt to taste. Juliennes of fresh ginger, a stick of cassia bark, a teaspoonful of sugar and a bay leaf are optional. Drain the soaked split masoor dal, add about 4 cups of warm water, and pressure cook for 25 minutes over low -medium heat. Remove from the heat, open the lid, allow to cool a little. Place a large sieve over a saucepan, and tip the contents of the pressure cooker into it. With the back of a wooden spoon, press out the tomato purée. Re-heat, adjust the seasonings, and serve with a few sprigs, or handfuls of fresh coriander and fried croutons.

All Food Styling: Kaveri Ponnapa

Image Credits: Nithin Sagi