Dotted across silent, grassy meadows in the northern valleys of Sikkim and the steep, cloud-covered slopes in Bhutan you find hundreds of tiny, intensely sweet wild strawberries lying at your feet. Plump, but fragile and easily crushed, they have a delicious, uninhibited sweetness so that one tends to eat far too many of them at one time. You can spend hours wandering, eyes glued to the ground, plucking these tiny treats and popping them into your mouth, while your hands soon turn sticky with the red juice.

The sweetness and description of this wild fruit fits the official description of Fragaria vesca, the alpine strawberry, which is native to the Himalayas. According to David Burton, a chronicler of the kitchens and tables of the Raj, it was this variety that was first introduced to cultivation in their kitchen gardens by homesick British empire-builders.

Since the other varieties of native strawberries: Fragaria indica, found in the lower Himalayas, and Fragaria nilgerrensis that grows in the South and East of the country are both described as lacking in flavour and sweetness, I imagine that the fruit that I ate in such copious quantities was the woodland strawberry, also known as fraisier des bois in France.

When strawberry cultivation first spread across the country, Mahabaleshwar got all the attention, as it still does, although the berries were grown successfully in several other parts, even in the plains. However, thanks to the prolific output and its weekly, Friday strawberry parties at the Club right through the season, Mahabaleshwar kept its reputation for the best strawberries, and the pleasures of eating strawberries were most often associated with the hills. Down South, in the kitchen gardens of the plantation homes of Ooty and Coonoor, wild, local strawberries thrived, along with a strong tradition of jam and wine making. Planters’ wives produced quantities of their own strawberry jam, served up at breakfast or as part of the teatime ritual, and there was not a plantation cook who could not make excellent jams.

A bucolic farm just outside Coonoor made enormous quantities of the most luscious strawberry jam I have ever tasted. We carried away as many jars as we could, and spooned the soft set jam over vanilla ice cream, watching it slide heavily down the sides of the scoop, leaving bits of whole red fruit in its wake and ate, transported by the combination, until sadly, the old gentleman who had made the jams by hand in huge vats passed on, and Beulah farm was sold.

Strawberry Salads, Strawberry Foams and several other desserts were popular, judging from the cookbooks of the colonial era. Colonel Kenny-Herbert gives an attractive sounding recipe for Strawberry Mould that may be perfect for the generous batch of jam I made from a consignment of particularly succulent summer strawberries. He describes it as a ‘simple and refined cold sweet’ and instructs us to “…dilute a pot of strawberry jam with sufficient water to make enough syrup to fill your mould, strain it, colour it a rosy pink with a drop or two of cochineal, and add a glass of liqueur or brandy; melt an ounce of gelatine, and strain it, when cold, into the syrup, stirring well.” This mixture is then poured into a chilled mould and set on ice for a couple of hours, turned out and served with ‘cold custard in glasses or iced cream’. He recommends adding to the attractiveness of the dessert by setting layers of whole fruit within it in the style of a jelly.

The strawberries I used were not those impossibly perfect, shapely fruit of Californian descent that you most often encounter these days, even those grown in this country. Instead, they were just a little battered, their leaves disheveled from travel, and they were of uneven size; some of the larger and heavier ones seemed to have sat on and gently squashed the smaller ones. They defied all the instructions I had ever read or heard about making jam. Their colour, however, was a deep, rich red, the fruit perfumed and impossibly sweet. So, I made the jam with a drastically reduced quantity of sugar. The fruit held just enough of its shape beautifully, during cooking, resulting in an intense natural flavour and colour: a deep, rich, glossy red that will look extremely well in a Herbert Kenny style Strawberry Mould. With its natural colour and flavour it will need help neither from cochineal nor brandy.

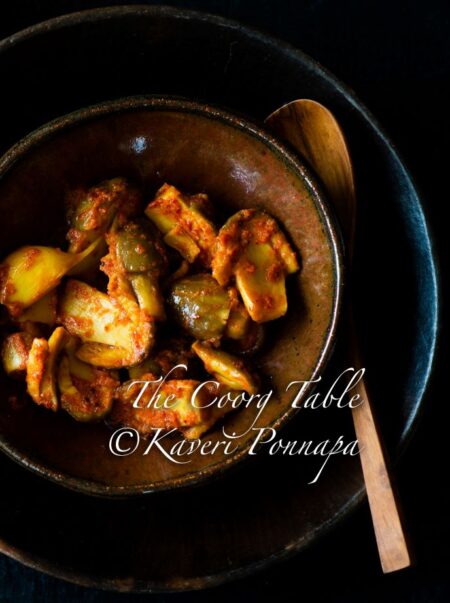

Strawberry Jam

- 1 kg fresh strawberries, hulled 500g granulated sugar 2 tablespoons lime juice Try not to wash the strawberries, but if you have to, give them a rapid rinse before hulling them. Place 2-3 china saucers in the freezer. Place the strawberries in a wide pan and crush the fruit lightly. Add the sugar and lime juice, stir well. Place over low heat and stir to dissolve the sugar completely. Raise the heat and bring to a boil. Stir frequently, lightly spoon off any scum that rises to the surface. When it begins to thicken, about 10-12 minutes, place a large drop on a cold saucer, return it to the freezer for a minute, then push against it with your finger. If it wrinkles, it is ready to set. Pour into a sterilized jar and seal immediately.

All Food Styling: Kaveri Ponnapa

Image Credits: Nithin Sagi